Jim Lampley apologizes to this Men's Journal writer shortly after hopping on a Zoom call to discuss his new memoir, IT HAPPENED! A Uniquely Lucky Life in Sports Television, and his upcoming blow-by-blow gig for Ring Magazine's outdoor triple-header in Times Square. That Friday assignment will mark his first since signing off on Dec. 8, 2018, when HBO abruptly exited the boxing business.

Lampley is preemptively apologizing while being informed that this writer had a chance encounter with him nearly a decade ago in the bowels of Madison Square Garden in New York City. Lampley, 76, can't recall if he was friendly (he most certainly was), but if he was unfriendly (he wasn't) it was because of his own near chance encounter with his now-former pal, President Donald J. Trump.

The exact details of that evening are fuzzy, but rest assure his mind remains exquisitely sharp outside of that night. He's agile and eloquently descriptive as ever. That much is evident while discussing his storied broadcasting career and, of course, the Sweet Science.

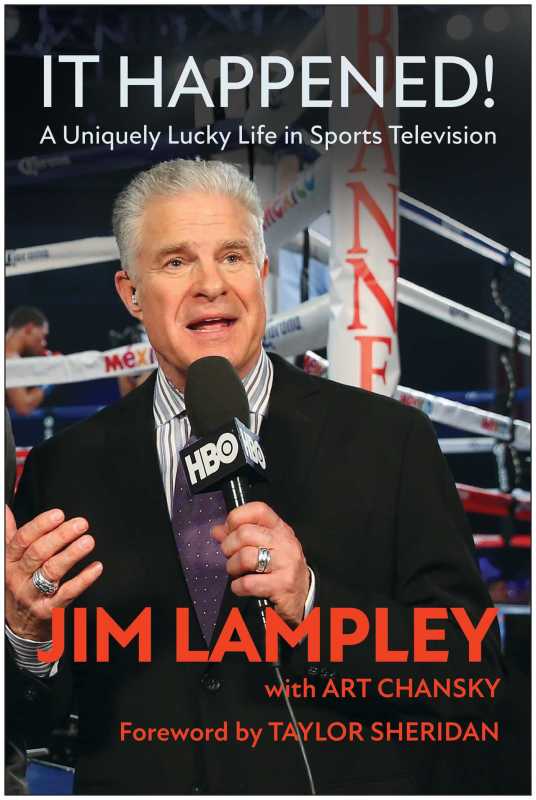

Simon & Schuster

Now, boxing fans can rejoice after the April 15 release of a memoir recounting his "uniquely lucky life" in sports; from experiencing his first core boxing memory in 1955 when his mom, Peggy, sat him down in front of a dinner tray and turned on the Sugar Ray Robinson-Bobo Olson fight for the middleweight championship; to calling the age-defying, 45-year-old George Foreman's improbable win over unbeaten 26-year-old Michael Moorer in 1994 to capture yet another heavyweight title.

Lampley also holds the distinction of having covered 14 Olympic Games, a record for an American broadcaster. He was there for the "Miracle on Ice" in Lake Placid, and he had a front-row seat to "The Dream Team" in Barcelona.

But the highest of highs also gave way to the lowest of lows on several occasions. Like when he got demoted two weeks after helming coverage of the 1996 Summer Olympics for "damaging quotes" he made to USA Today after the Olympic Park bombing, in which he suggested that his co-host, Hannah Storm, deferred to him as NBC's "lead dog" for its news coverage of the bombing. The misstep proved painful. Like a shot to the liver, the demotion landed him in Daytona Beach, Fla., to call — of all things — the U.S. Cheerleading Championships.

He thought his career was over.

He thought there was no way to recover.

He fell into an abyss so deep only one dear friend was capable of pulling him out unscathed thanks to his sage advice: Jack Nicholson.

Lampley is the first one to tell you that luck, as much as preparation, is the driving force behind his broadcasting career. By sheer luck, Lampley found himself calling boxing on ABC Sports when then-president Dennis Swanson sought to drive him away from his lucrative deal and make him quit by assigning him to a sport that would make him look like a fish out of water.

Unbeknownst to Swanson, Lampley had been a lifelong boxing fan. He would eventually replace his good friend and blow-by-blow legend, Barry Tompkins as the face and voice of HBO Championship Boxing for 30 years, from 1988 to 2018, a byproduct of an unparalleled work ethic Lampley exuded in his early days of calling boxing at ABC Sports. That relentless drive to excel caught the eye of one Ross Greenburg, a production assistant at ABC Sports who would later rise to become executive producer of countless boxing telecasts and president of HBO Sports.

The best blow-by-blow announcers are succinct, yet descriptive. They're studious and knowledgable, but not condescending. They're prolific storytellers, never attention seekers. And Lampley personifies each of those qualities.

Jim Lampley recalling that famous night when he made that iconic call

— Hamed (@HamedBoxing) March 22, 2025

“It Happened” when the impossible happened!

George Foreman famously became the oldest ever Heavyweight World Champion at age 45, by dethroning Michael Moorer in November 1994.

📷 @ArielHelwani pic.twitter.com/U00sVudkp8

"Every fight is like a mini-movie with subplots surfacing round by round. Jim Lampley had a keen sense of each fighter's history, understood their individual stories, could put each fight into instant historic reference, had a photographic memory that recorded each fight of every fighter into his brilliant mind," Greenburg tells Men's Journal.

"And then, he could magically meet the moment of a big fight, whether uttering the phrase 'Mike Tyson has been knocked out' when Buster [Douglas] finished him off in the 10th round, or 'It happened ... It happened' when George Foreman shocked the world and at 46 knocked out Michael Moorer. The great, iconic, legendary announcers, in any sport, put the entire story of a fight or a game in penetrating focus for the viewer, and then when the moment comes they communicate the high drama in a scintillating fashion."

Thanks to Turki Al-Sheikh, boxing's most powerful figure and the chairman of Saudi Arabia's General Entertainment Authority, Lampley will make his ringside comeback on Friday for Ring Magazine's outdoor triple-header card, featuring Ryan Garcia, Teofimo Lopez, and Devin Haney, in separate bouts, live from Times Square on DAZN PPV.

Men's Journal recently caught up with him to discuss his legendary career.

You probably won't remember but we met nearly a decade ago at Madison Square Garden.

I hope I was friendly and not unfriendly. If I was unfriendly that was because that was the last time I came face to face with Donald Trump. That night, my one-time friend and acquaintance Donald Trump, with whom I socialized, drank, ate, etcetera, for years, strolled onto the floor of the Garden and walked around kind of casing the joint to see the response. And I was watching him.

At one point he turned around he caught my eye. And he smiled. He kind of raised his eyebrows. And he started walking right toward me. This is 2016. We’re in the middle of the presidential campaign, and he’s walking toward me with this look that says, ‘OK, now I’m going to have a positive conversation with my old friend here. Talk about my candidacy, whatever, etcetera.’ And I proceed to dive into my paperwork in front of me and do everything possible to avert my look. And to his credit he gets the message and turns around and goes walking in some other direction to do something else. And that was the last time I was ever face to face with Donald Trump.

And it was interesting because, just with body language and my look and the way I treated it, I offloaded the whole friendship, which had preceded. And I made clear to him my political predilection with regard to his candidacy for the presidency. I probably showed him how lunatic I thought that whole enterprise was, and I’ve never been in that position again. Now, who knows. It could happen again in the future. It was, in a way, a trying moment for me, ‘How exactly am I going to handle this?’ So, I don’t know that I honored or dishonored myself. It was probably somewhere in the middle.

One thing I mentioned to you when we met is that the Mexican community in Los Angeles admires you. I wanted to underscore that notion when we met because of all that you've done for the boxing community, our community, their fighters, and my generation.

I really appreciate that comment. And thank you very much. At the risk of taking too much of your time, it has been an ongoing through line in my boxing-based career that I had that particular positive relationship with the Hispanic community. And I owe it all to an eighth-grade Spanish teacher at South Miami Junior High School, whose name was Mrs. Summer. And I don’t know what Mrs. Summer’s Hispanic derivation was, but from her appearance I know that she was of Hispanic decent in some way, shape or form.

Mrs. Summer, in her introductory eighth-grade Spanish course, which I had to take, was fanatical about pronunciation. So, the result of her teaching in that fanaticism about pronunciation was that when Oscar first became a major public figure and everybody else was saying "Oscar De La Ho-LLA," I was the one who said, "Oscar De La Oh-yuh" and lightened up the H and pronounced it the right way as I understood it from Mrs. Summer.

And there was a moment after a few fights when Oscar pulled me aside after a fight or meeting and said, "You know, I can’t tell you how much I appreciate that you properly pronounce my name." He said, "No other Anglo reporter gets it right. They all hammer the H and you’re the one who understands that it’s supposed to be silent. And oh, by the way, my father appreciates that, too." So, I’ve always tried to be true to Mrs. Summer’s teachings and to pronounce all the Hispanic names in the classically correct way. And I’ve had tremendous relationships with Hispanic fighters.

Do you view Friday's call on DAZN as a comeback or are you viewing it as if you're stepping back into it as if you've never left given your work on PPV.com?

I think it’s a comeback and I think I have to prepare as though it’s a comeback. I can’t go in with the complacent, self-satisfied attitude that just because I'm stepping back into the chair I’m sure as good as I always was. No, that’s not the case. I can’t possibly be sure that I’m as good as I always was. Maybe six or seven rounds in I can give you a temperature reading or feedback report on that kind of thing, but to me it’s a meaningful test of how much of my understanding of boxing and my instincts for understanding boxing I've managed to hold on to, and how rapidly I can regain my bearings in calling a fight.

It’s a unique kind of television sports commentary. And I am confident. I wouldn’t say that I wasn't confident. I wouldn’t have agreed to this particular threshold and new arrangement if I weren’t confident. But the last thing in the world I should want to be is over confident. I need to go in extremely respectful of the fact this is a unique kind of television sports commentary. Yes, there was a long period of time when I was seen by a lot of the audience as being very, very good at it, and now I need to go at it second-by-second, minute-by-minute, piece-by-piece, word-by-word and make sure I can still do exactly what I did.

If there's a villain in your memoir it's former ABC Sports President Dennis Swanson, whom you say did everything in his power to drive you to quit. Unbeknownst to him, Swanson moved you to boxing in hopes of seeing you struggle, but that move led you down a career path that earned you fame and etched your name in boxing lore. So, in some respect, do you kind of thank him for that?

Irony upon irony. It’s almost Shakespearean. He arrives at ABC Sports having been the stations division executive. His big credential was that he had, as the chief executive of WLS-TV Chicago, given a talk show slot to a woman named Oprah Winfrey. Good credential. And so, he arrives at ABC Sports with a reputation for knowing talent, and his one predilection with regard to the talent lineup at ABC Sports is, "Why is Jim Lampley in these positions of prominence and prestige, and how do I get rid of him?"

He looks at me and my personal style and decides, "No way in the world will he ever fit in boxing. He’s going to be a fish out of water in boxing, and the audience will see him as the successor to [legendary broadcaster Howard] Cosell." I had already suffered a few years before from having been Cosell’s successor on Monday Night Football halftime highlights. That was not exactly a great moment for me. Whether Swanson knew that or didn’t know that, he chose to assign me to boxing. He openly told my agent, "I’m doing this to get rid of him." His reason to want to get rid of me — his biggest reason — was that I had guarantees in my contract regarding my Olympics arc that he didn’t believe he could tolerate. He just absolutely wasn’t going to allow me to climb the ladder at the Olympics toward the perch that was written into my deals. So, he couldn’t just fire me. He had to get me to voluntarily walk away.

And so he assigned me to boxing. And he did not realize or pay attention to the fact that Alex Wallau, who was running the boxing franchise as an executive for ABC Sports, had signed a get-acquainted, looksy contract with a 19-year-old heavyweight from upstate New York whose name was Mike Tyson. As I’m sure you know, Miguel, my first network television boxing appearance was blow-by-blow for Mike Tyson versus Jesse Ferguson, the famous, "I want to drive his nose-bone into his brain," fight.

And when Mike said that in the post-fight interview I was standing at ringside saying to myself, silently, "Look at this. Look at what I have now happened into. This kid is not only gonna be the greatest quote machine in boxing, he’s gonna to be the greatest quote machine in sports." ... Later, ironically, Swanson gets attracted to NBC by Dick Ebersol, who had been Roone Arledge’s assistant at ABC, who had run the initial talent hunt for the college age reporter that produced my first network television exposure in 1974. And in constructing NBC’s approach to the Olympics, Dick reaches out and says, "We’re adding hundreds of hours of cable television coverage. It’ll be on both MSNBC and CNBC, and I want you to be the central host. I want you to be in the chair for all these hours of programming and launch our cable project."

And I thought about it. I eventually said, "Yeah, Dick, I think that’s good. I think I want to do that." And he said, "Oh, one more thing I should tell you, I have hired Dennis Swanson to be the chairman of the cable project." I said, "You've hired Dennis Swanson to be the chairman of the cable project and you want me to be the central identifiable host?" And he said, "Yes. And I can tell you without equivocation that Dennis totally agrees you are exactly the right person for the job and he wants you just as badly as I do. And I know that you probably do not believe that, but I assure you that, ultimately, you will hear that from him."

And I trusted Ebersol enough that I decided to take his word for it. And I took the gig. Then it led to several more Olympics that helped me to that totem pole marker of 14 Olympics that, I’m told, no other American broadcaster reached. But at the end of the day I wound up hosting in Sydney, Salt Lake City, Athens, Torino, and in Beijing, all of those Olympics with Dennis Swanson sitting in my control room, every minute of every hour.

And we began every day with, "Hello, Dennis. Hello, Jim." And we ended every day with, "Good night, Dennis. Good night Jim." And no other words passed between us. But it’s a tremendous lesson in corporate life and in the way network television sports used to be. The same fools that you meet on the way up you’re gonna see them on the way down, too. So, the simple fact that I could not get away from Dennis Swanson after he had tried to destroy my career was, at first, meddlesome and rankling, and then eventually amusing, and in some ways reassuring. It was everything all wrapped into one package.

As a journalist you’re taught to show no emotion, to not have a rooting interest, and remain objective. But watching you become emotional on TV, from eulogizing your friend Muhammad Ali or paying homage to Miguel Cotto and Juan Manuel Marquez’s long and honorable careers, is being overcome with emotion a constant struggle you deal with when you’re in front of the camera?

Well, there was supposed to be a wall there. And I had many experiences, both as a sports host and anchor and also as a news anchor in Los Angeles. When I learned how incapable I was of sustaining and maintaining that wall in certain situations. The very first day I ever went on the air at KCBS-TV as a news anchor, a lone gunman named Patrick Edward Purdy walked onto a school yard in Stockton, CA and shot 22 elementary school children. And I had to host a few hours of coverage of that situation live. And I was not able to fight off the tears. It was just too devastating to me. And the news director and the people at the assignment desk were very upset. You know, "You can’t do that. You’re not supposed to do that." And the audience response was overwhelmingly positive. "Thank you for being a real human being."

So, I learned that if you are convincing enough and if you were real, you could have it both ways. You could deliver the information. You could, in some ways, walk the middle line that made you seem like a purely objective observer. But you could also underline that with a subtitle that sort of said, "I’m a human being, too. I’m just like you at home." And I got away with it. You’ve mentioned all those boxing-related moments when I broke the wall. And every single time I would finish the telecast I would rebuke myself. I would say to Ross Greenburg or one of the other producers, Dave Harmon, Rick Bernstein, I would say to them, "I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to get that emotional." By that point, everybody knew me. And most of the people on the telecast would say, "Jim, stop it. The audience knows who you are. The audience loves and appreciates who you are. Don’t stop being who you are. If other people can do this better than you, that’s OK. But at the end of the day, we hired you to be you. The audience wants you to be you, and they know that from time to time they’re going to see that."

I don’t want this to sound sexist or gratuitist, but as you know from reading the book I was raised by women. I wasn't raised by men. I was raised by women. And my mother was a deeply emotional Irish-American girl, who taught me that to muscle down and subvert your own feelings was not the right way to live.

If my heart said cry, my job was to cry. And to this day, I can’t stop it when it starts. And I no longer really try to stop it. You can see that I’m glistening right now because I can’t talk about my mother without getting that way. I can’t think about her sitting me down to watch Sugar Ray Robinson versus Bobo Olson in 1955. I can’t think about her dropping me off at the Miami Beach Convention Center for Cassius Clay versus Sonny Liston, Feb. 25, 1964 without feeling this way. It’s a part of the experience. So, sure, would I like never to have cried on the air. I would love that. Would that be me? No.

After the O.J. Simpson verdict was announced on Oct. 3, 1995, you write in the book that you raced to the Lakeside Country Club to look for none other than Jack Nicholson, a boxing fanatic who became a close personal friend. Later in the book you write that Jack "rescued me emotionally and saved my career." How so?

He saved my career. That’s the bottom line on Jack and me. He saved my career. He saved my career at a moment when I was so down, so bereft. I thought that I had totally blown everything. And I went to him because I knew he had the most educated and thoughtful long-term perspective on what it is to be a public figure and to perform on camera for a living. And he told me two things that I kept with me that helped to save my career, and the first was there are no small parts, only small actors. If they’re going to send you to cover the United States Cheerleading Championships — and Dick Ebersol was in fact doing that after the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta — if that’s the assignment, your job is to be the greatest cheerleading championships commentator of all time, that’s all there is to it. And the second one, which was even more helpful, was longevity is lovability. And I’m living through that right now.

Longevity is lovability. The reason that people are excited and interested in my return to blow-by-blow on this new television venture right now, the reason that that causes a ripple among the boxing audience is because longevity is lovability. They heard me calling fights for 31 years, and on that basis they want to hear me again.

THE RING IN TIMES SQUARE 👀

— Ring Magazine (@ringmagazine) April 29, 2025

Can’t wait for fight night 🔜 🍿

Buy FATAL FURY: City of the Wolves out now and watch The Ring’s @FATALFURY_PR card LIVE on DAZN this Friday 🍿 pic.twitter.com/L5DF7MlgTE

As a boxing fan, I still can't wrap my head around HBO abandoning boxing. For more than three decades they were synonymous entities. Not only did fans lose Boxing After Dark and Pay-Per-View bouts, but also brilliant productions like the docuseries 24/7 and your in-depth series, The Fight Game.

HBO was a culture and a group of people who worked with each other and influenced each other’s attitudes about artistry over a long period of time, and then eventually the company was bought by, as I like to say, a bunch of cell phone salesmen from Dallas. It was a far different ethos and a far different group of people.

I believe it’s in the book, how one night at [a post-Emmy party in Los Angeles], the chairman of HBO, Richard Plepler, suggested, "Why don’t you go walk over there and talk to that guy in the grey suit. He’s your new boss." I took his advice, I went over there, spoke to John Stankey, who is [still] the chief executive of AT&T, which was buying the company at that time. And all due respect to Stankey, I’m sure he’s great at what he does, but I went over and had a 15-minute-get-acquainted introductory conversation with him and I went back to Richard’s table and Richard said, "How did that go?’ And I said, ‘Well, as far as I can tell boxing is dead."

He said, "That was my impression, too. Just wanted to make sure we were on the same page." And sure enough, we were right. And boxing was dead. I wish I knew the reason why. I wish I knew what quantification or cultural observation prompted them to say, "We, as we reshape this into the new thing, Max, should get rid of boxing." I didn’t get it then, and I don’t get it now. It’s their game now. They bought it. They have the right to do whatever they want to do.

And maybe they can point to balance sheet evidence or some other indicator that says, "Aha, we did exactly the right thing to get rid of boxing." But I don’t believe that. I think that it was an important characteristic of HBO. I think it was an important touchstone for the viewer. It was drama. It was unpredictable live drama. It was exactly what a drama-based television network should have. It was different from all of the conventional team sports that we see so much of on all of the other networks.

It was something that both paid cable networks, Showtime and HBO, built around and promoted around because they recognized these are human dramas. They are cellular in nature. They are not like anything else in sports, where it’s far more organizational and institutional.

This is about two human beings who go into the ring and breathe on each other and taste each other’s sweat and blood and try to prove minute-by-minute "I’m more man than you are." There’s nothing like that. And to have wiped it off the face of the television screen to the degree that they did, I don’t get it.

And I never will.

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/5WPIhE2

No comments:

Post a Comment