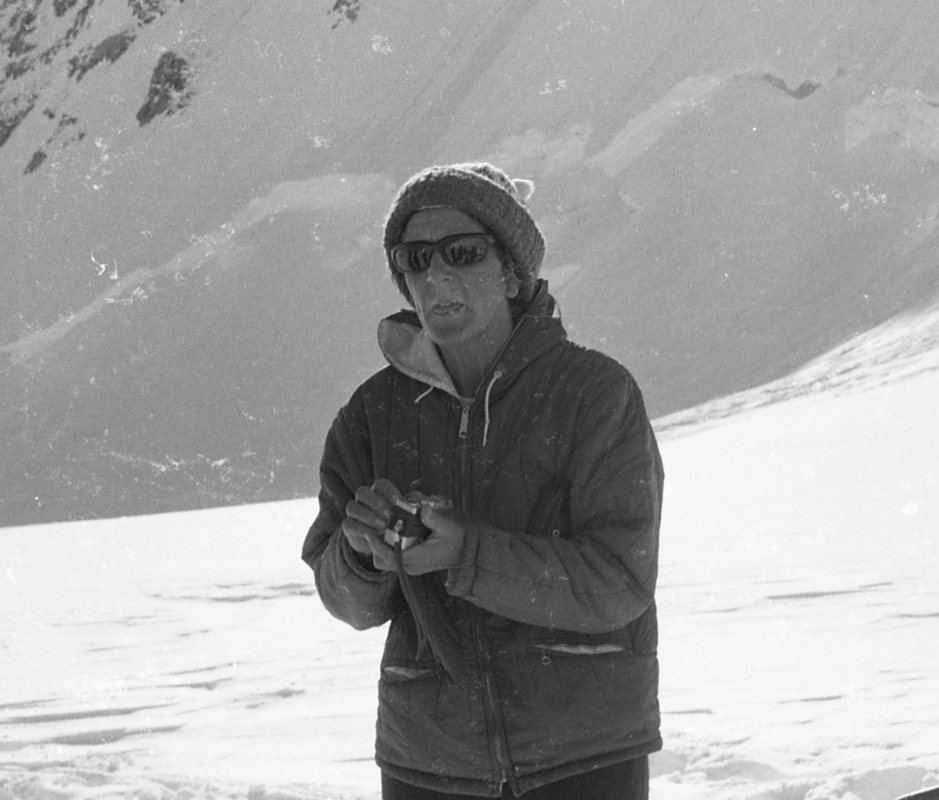

Margaret Clark; Courtesy Image

In 1967, Alaskan mountaineer and doctor Grace Hoeman was the only woman on two separate Denali expeditions. She was turned back on both.

The first time, the team leader sent her back midway up the mountain. He claimed he suspected she was suffering from altitude sickness—even though seven mountaineers from another party above them had disappeared into a nightmare storm that broke over the summit, and a doctor might be critically needed. All seven ended up dying.

A month later, Grace’s husband Vin—a renowned mountaineer and a member of the Alaskan Rescue Group—organized an expedition, which included Grace, to recover the bodies. This time, Vin turned her back after only two days. Those incidents along with the one below would spur Grace to develop a bold idea: to lead the first all-women’s team up the great mountain.

Two months after Vin Hoeman returned from Denali in August 1967—a failed attempt to find the bodies of the lost members of the Wilcox team—mountaineer Boyd Everett invited him on an expedition to climb K-2 in the Pakistani Himalaya. Everett was a young New York investment banker who so looked and acted the part that his colleagues would have been shocked to discover he spent most of his free time climbing remote peaks in Alaska and the Yukon.

Neither Everett nor Vin had climbed in the Himalayas though, and Everett asked Vin’s thoughts on other climbers to add to the team. Vin sent back the names of some Alaskan mountaineers, and then he and his wife, Grace, left for South America to climb 20,702-foot Chimborazo, an ancient volcano in Ecuador. The main purpose, Vin said, was to test Grace’s altitude tolerance.

On Chimborazo, the pair were held down by a storm at 18,000 feet and confined to a tiny tent for four days. Twice, pieces of the tent started to rip in the hungry wind, and they tied up the material to prevent further damage to their shelter. Vin read the entirety of Gone With the Wind aloud to pass time. Once the tempest let up, they returned to a lower camp at 15,700 feet for more supplies. From there, Grace and Vin climbed to the summit and back down in a single fourteen-hour push. Vin promptly wrote to Everett suggesting Grace for the Himalayan expedition as the team doctor.

“She acclimated slowly but does conquer her altitude sickness. Not many women have been that high and fewer yet could do such a summit day.” He enclosed Grace’s climbing resume along with the letter.

Over the next months, delays and red tape with permits on K-2 forced a pivot in Everett's plans. He chose to climb Dhaulagiri 1 in Nepal instead, the world’s seventh-highest mountain, which some climbers considered the most difficult of the 8,000-meter peaks. Everett screened and finalized the team accordingly.

Grace wasn't to be part of it. She had “light experience,” Everett wrote to Vin. She must've been suffering “illusions of grandeur” to think she might join a Himalayan expedition. Grace was insulted and outraged. Vin defended her heatedly. Other members of the team didn't have her depth of experience, which extended for thirty years over four continents, including several first ascents.

“Let’s face it,” he wrote to Everett, “some member or members of our group don’t want a woman sharing what they consider a man’s adventure.”

Margaret Clark; Courtesy Image

Everett apologized for his phraseology. “Illusions of grandeur” wasn’t diplomatic, he said. The rejection was nothing personal to Grace. It was the men who were worried about themselves, about “being inhibited by the presence of a woman high on the peak.” And how would the other married men explain to their wives that they had to stay home while Vin’s wife got to come? Surely Vin appreciated his problem, Everett wrote.

They dropped the matter and got on with preparations.

In early April 1969, Vin left with the fourteen-man Everett Expedition to climb Dhaulagiri. Everett aimed for the never-attempted southeast ridge, a knifelike rib that led to the summit at 26,795 feet. They’d been sponsored by National Geographic. The team spent three weeks securing and organizing supplies in Kathmandu and trekking to the base of the mountain. The first sight of the peak staggered them: a fractal pyramid of steep stone and ice, isolated in its imposing immensity from the rest of the massif.

“We had considered ourselves mentally prepared for such a mountain,” expedition member Al Read wrote. “But this was bigger, more savage and forbidding than anything our imaginations conceived.”

Halfway across the world back in Alaska, that dangerous southeast ridge of the Himalayan giant played on Grace’s mind. She wrote to Vin, via the American embassy in Kathmandu, that it worried her. She wrote of being lonesome, of a terrible feeling, and that perhaps she should have just gone along at her own expense to be with Vin—what could the team have done about it, really?

Vin wrote back that she had no idea how lonesome he was for her, and that he and Grace on their own would be farther ahead in the climb than such an unwieldy expedition. He missed her and was “anxious to get this expedition over with.”

She replied, “I seem to be just as unhappy without you as you are without me. We can threaten each other with separation, desertion, etc., and we are heartbroken without each other. I wish you were back here.” She relayed the ascents she’d done with others in his absence, including leading risky segments of climbs—and details about some fellow climbers readying for a Denali attempt. She hoped to go with them. “I’d like to wipe out the dark spot of not having climbed Denali.”

She told him that an article he had requested from Austrian climber Kurt Diemberger, the first to ascend Dhaulagiri, nine years before, had arrived. “Apparently you started too late,” Grace wrote. “‘The ridge is endless,’ he writes, ‘and without luck you will not get to the summit.’ The weather and particularly the wind are intolerable, according to him.”

In another letter, she wrote that she’d suddenly had a vision of him with frostbitten toes. It was horrible, she wrote: “You’re the only thing worthwhile to me in this world...Be careful.”

During the last days of April on Dhaulagiri, Vin and Louis Reichardt, who’d been sharing a tent and trading stories from past expeditions, acted as an advance team to explore the route. At 17,000 feet, at the rim of a broad basin, they discovered a wide crevasse that blocked their progress up the glacier.

The whole team carried logs up from base camp at 12,000 feet to build a bridge over it, and then half of the climbers retreated back to base camp while eight members, including Vin, Reichardt, and Everett, remained at the high camp to craft the bridge the following day.

They passed the night sharing stories to the background music of taped symphonies that Everett had brought. On April 28, they set out on a sunny morning for the crevasse, balancing the twelve-foot logs on their packs. As the team, split between either side of the crevasse, finished positioning the timber, a great roar cracked the alpine quiet.

Avalanche.

They had but an instant to scramble for cover. Reichardt found only a meager change in slope degree, dove down, and covered his neck with his hands. Pieces of debris pummeled his back, but none with force enough to even dislodge his grip, let alone bury him. When the roar finally faded, he felt relief they had been let off so lightly by the fury of the mountain.

Then he stood. The world he looked upon was an entirely different one than from a moment before. It had been redefined by the violence of the ice cliff that had collapsed just above. All the equipment—packs, climbing gear, logs, ropes—was gone. Gone even was the snow the team had been standing on. The ground had been scoured to dirty glacial ice. The huge avalanche had cut a hundred-foot swath in its savage trajectory across the basin, and filled the great crevasse entirely with ice.

Gone were his seven companions. Reichardt was alone in the horrible silence.

On April 29, in Anchorage, Grace mailed a letter to Vin. “This must serve to tell you how much I love you,” she wrote, “and how concerned I am about this endeavor, wishing every day it were over already...No mountain is worth it…Come home soon.”

The telegram from Nepal reached her the next day.

On the mountain, the remaining members searched thoroughly, long, and with ebbing hope. What few pieces of equipment they found were totally destroyed. The bodies of the seven men engulfed in the avalanche had vanished entirely.

Margaret Clark; Courtesy Image

Two of the surviving climbers wrote to Grace a few days later on letterhead that read Boyd N. Everett, Jr., Expedition Leader, letterhead that would never see Everett's own writing again, with an account of the accident.

“Vin’s body lies under tons of ice and snow beneath Dhaulagiri,” they concluded. “There is no more noble monument—there is no prouder resting place.”

It was cold comfort to Grace.

In the days following her husband’s death, Grace was inundated with letters from friends and family, both her own and her husband’s, and from the wives and girlfriends of the other men killed. Dave Seidman’s fiancé wrote, “The neat black print that says they’re dead is hard for me to believe. But this I do believe: they lived. Every vibrant, aspiration-filled day. I grieve for us all.”

Grace was adrift in bottomless grief. In her replies, she wrote of her regret that she wasn’t with him on the mountain when he died, that she had tried to prevent him from going at all after so many misgivings. “A ghastly bitterness will stay with me for the rest of my life.”

A week after Vin’s death, she opened his climbing journal. Under the last entries in his writing, she recorded her own climbs she’d done while he was in Nepal. It’s the first time her handwriting appears in the meticulously kept book. Under those entries, she wrote “Dhaulagiri, 17500, E Dhaulagiri Glacier,” and drew a cross. And then she drew a line, and wrote: “From here on, Grace without Vin.”

As the months passed, Grace brooded on and internalized her rejection from the Dhaulagiri team as the reason for Vin’s death; had she been there, she would have made different choices that wouldn't have led to them being in that fatefully violent spot. She went so far as to request the journals of the men on the team in order to analyze the incident. She was looking for a target to blame, an outlet toward which to direct her agony.

She also believed that women could be a cautionary, calm presence on mountain pursuits, and had she been there, the choices that led to his death wouldn't have been made. She wasn't entirely wrong. Recent research has shown that in adventure situations, men are more likely to engage in riskier behaviors, women are less likely to die in avalanches than men in alpine pursuits, and all-female groups make safer decisions than all-male groups or mixed groups.

Grace’s presence may not have saved Vin on Dhaulagiri. But in her mind, it'd already become a truth that wouldn't leave her alone.

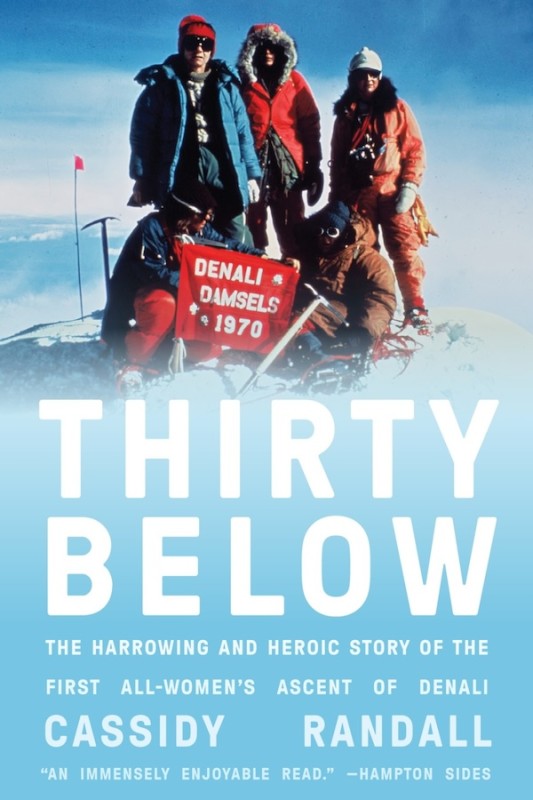

Courtesy Image

Cassidy Randall's new book, Thirty Below, tells the story of the first all-women expedition to climb Denali. Popular belief held that women were incapable of withstanding high altitudes, savage elements, and carrying heavy loads. Which made the defiant idea of one climber, Alaskan mountaineer and doctor Grace Hoeman, all the more audacious. Everyone told Grace and her six-woman team that it couldn’t be done. Then, when disaster struck at the worst time, the team’s actions would decide not only their fate, but how the world would judge them—and all women’s ability to climb and survive the fiercest mountains.

Related: Alaska's Wildest, Weirdest Frontier

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/RMcuhw6

No comments:

Post a Comment