ALL GOOD ART, as the adage goes, is political. From Diego Rivera to Pablo Picasso to Walker Evans to Banksy, artists have never shied away from creating works with political points of view. Now they’re casting their gaze on perhaps the single greatest threat to humankind—global climate change. In the coming generation, coastal cities will need to grapple with sea level rises as polar ice caps melt. Freshwater shortages could create waves of refugees. And changes to the climate, combined with the increasing effects of human influence on the environment, could mean the extinction of up to a million species. It’s a sobering time, to say the least. But for this new collection of painters, photographers, designers, and graphic artists, it’s also an opportunity to make new work that not only strikes an emotional chord but persuades viewers into action. That is to say, to create work with political ends. Here are the artists doing their best to make sense of the coming environmental disasters—and spur the world into positive change.

Zaria Forman

Capturing the Beauty of Polar Ice Before It’s Too Late

OVER THE last decade, Brooklyn artist Zaria Forman has become renowned for hyperrealistic drawings of water in dramatic transitions—waves crashing on the beach, rainstorms thrashing the sea, icebergs shimmering as they melt. There was only one problem: “At first, I was actually terrified to draw ice.” she says. “I didn’t think it was possible to render in my chosen medium.” That’s a valid concern, considering that Forman uses pastels, basically colored chalk. Today, though, she’s finished dozens of stunning images of glaciers, thanks to numerous trips to the polar regions.

It was her first trip to the Arctic, in 2007, that got her interested in the subject. Based in Greenland for a month, she ventured out into the ice fields each day, where the people she encountered—scientists, reporters, government officials—were already focused on how the landscape was changing. Vast fjords were not freezing as they once did, which impacted the locals’ subsistence hunting. “It opened my eyes to the climate crisis,” she says, “and it instilled in me a need to play a part in helping to solve it.”

It wasn’t until 2012, however, that Forman turned her creative energies back to ice. She returned to Greenland to lead an expedition honoring her recently deceased mother, an artist herself. “I decided it was time to face my fear,” she says, “and I’ve been drawing ice ever since.”

For her work, Forman spends at least a month on location, making sketches and taking thousands of photographs, before sitting down when she returns home to draw large-scale interpretations of the photos. The meticulous drawings can take upwards of five months to complete. That translates into a lot of time in the studio—and in the field. Forman has trekked on a glacier with a Greenlandic shaman, climbed through an ice cave in Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, and flown with NASA scientists over areas of Antarctica where rescue would have been nearly impossible. She’s also been to the Maldives—the lowest, flattest country in the world, because melting ice leads to rising seas.

Forman wants her art—which has been displayed in museums, U.S. embassies, and NATO’s headquarters in Brussels—to help people connect emotionally to places that are on the front lines of climate change. “I choose to convey the beauty as opposed to the devastation of threatened places,” she says, “because I want to inspire the viewer into positive action, not paralyze them with fear.”

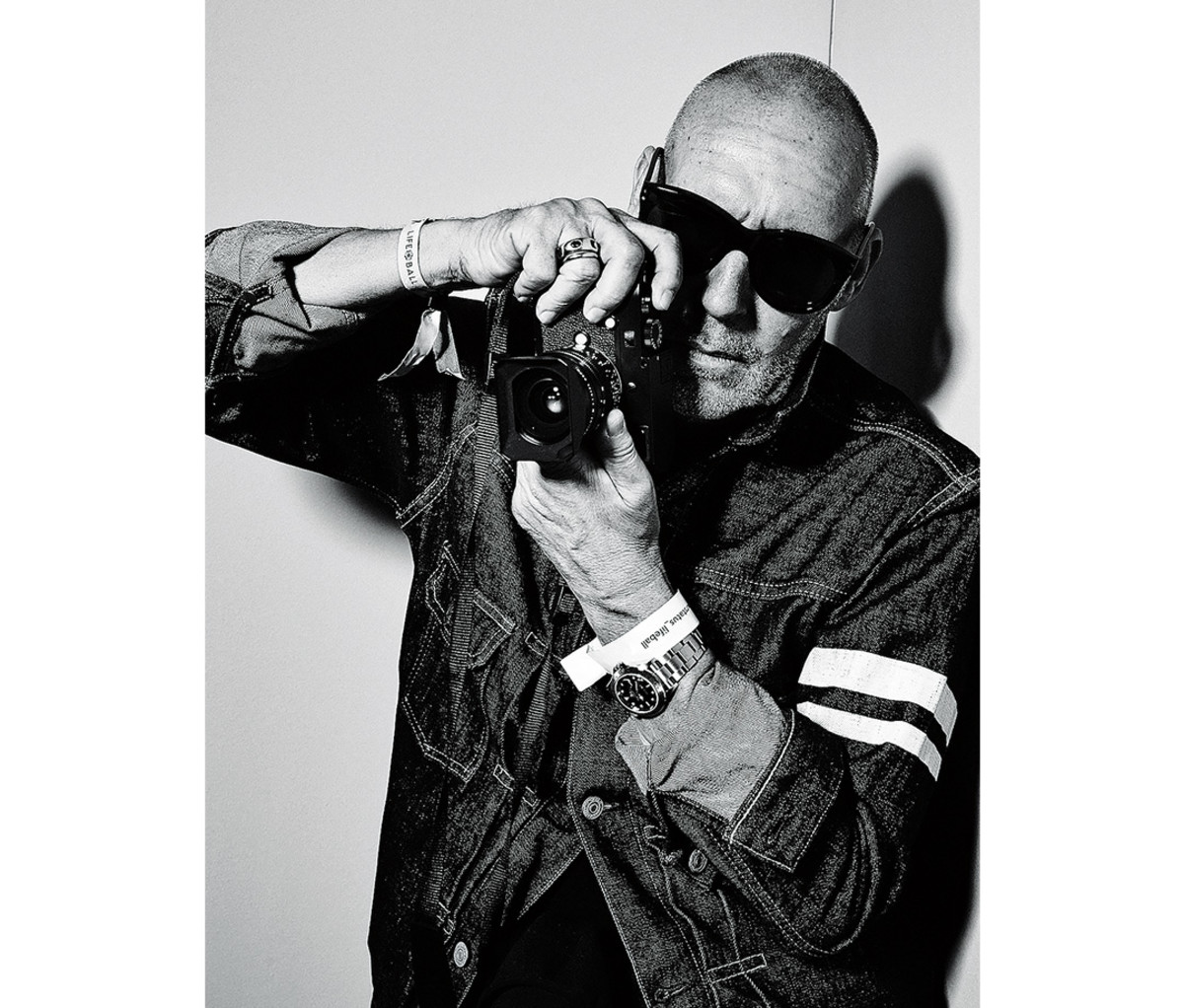

Michel Comte

A Fashion Photographer Returns to His Outdoor Roots

A DOZEN YEARS ago, Michel Comte was at the peak of his career as one of the most successful fashion and portrait photographers in the world. His work appeared in practically every glossy magazine and featured a glowing roster of A-list celebrities and models, including Sophia Loren, Cindy Crawford, and Tina Turner. But he yearned to return to his roots as a painter and sculptor and focus on the state of the natural world, particularly its ice.

“My childhood outdoors had a very large impact on my life,” says Comte, who was an avid skier and mountain climber growing up in Zurich. In 1986, he spent nearly a year in the Himalayas, where he trekked to some of the world’s most beautiful glaciers, occasionally photographing them by dangling from a hang glider. He even climbed on K2 and made it to Camp 3, at 23,000 feet. “I was a very committed mountain climber until one of my very closest friends got killed,” he says. “Then I took it more as an exploration than as a sport.”

Comte’s love of icy landscapes was sparked by the first aerial images of Swiss glaciers, taken in 1914. His grandfather, Alfred, was a co-founder of Swissair and the photos were shot by Alfred’s co-pilot. Many of those glaciers have changed drastically, including St. Moritz’s Roseg Glacier, which Comte still visits regularly. “Glaciers are not white anymore in the summer,” he says. “They are mostly gray from all of the carbon output.” He used this idea in one of his most recent works, a series of paintings of discolored glaciers.

Reinventing himself professionally was not easy. Comte was so established as a photographer that he had to submit his work anonymously to museums to help it get accepted. It worked. His first major installation, Light, was at the MAXXI Museum of Modern Art in Rome, in 2017. It was an homage to glacial landscapes in Switzerland, the Himalayas, Canada, Africa, and Norway through large sculptures, photos, video installations, projections, and even mini ice mountains melting away in the gallery. Then came Black Light, White Light, in Milan, in which he created Glacier Lake, a reflecting pool filled with crinkled silver thermal blankets resembling ice chunks. A subsequent, more ambitious project used those blankets to cover and protect real glaciers in summer. It was the beginning of an ongoing shift from museum work to getting his art—and his viewers—out into the wild, where they can do something.

“The only way we can make change is to get actively involved,” says Comte. “Then you really start seeing what is happening.”

Alexis Rockman

A Surreal Take on Human Influences

“THERE IS NOTHING more compelling and alarming than human history and how it has affected the rest of life on Earth,” says New York painter Alexis Rockman, whose work has been focused on environmental change since 1995. “Geology, human engineering, and disease have all had a hand in our evolution as a species and shaped our world.” His recent touring exhibition, The Great Lakes Cycle, dramatizes how the Great Lakes, which hold 20 percent of the Earth’s surface fresh water, are being impacted by human activity. Forces of Change, for example (above), is a composite of significant places and people from Great Lakes history, from the Niagara River to the invasive tree of heaven. “The great disrupter, E. coli, is presented as a tentacled, monstrous kraken that bursts from the river’s bottom,” says Rockman. “It alludes to the powerful forces that often seem invisible to us.”

Eve Mosher

Visualizing a Watery World

WHEN EVE MOSHER chalked a blue line across New York City in 2007, she was full of optimism. Marking the ground in areas that were 10 feet above sea level showed where flooding could reach as sea levels rose and supercharged storms hit. The idea was to show urban residents how climate change would impact their lives—and inspire positive action. But in 2012, when Hurricane Sandy flooded parts of New York City, HighWaterLine seemed prophetic. The conceptual artist has now taken that idea to other cities, including Miami and Bristol, England. “Artists can help people imagine and move forward,” says Mosher. “We are at risk of going extinct. We need to have radical courage about what’s possible to reimagine the future.”

Joel Sartore

Documenting the World’s Disappearing Species

OVER THE LAST 13 years, Joel Sartore, a photographer for National Geographic, has made images of 10,000 of the roughly 15,000 species living in zoos and nature preserves around the world. But these are no ordinary photos. For each animal, he uses a mobile studio setup, capturing them on a white or black background. This is done to level the playing field, as he says, in terms of size. “The mouse is every bit as important as an elephant,” says Sartore.

The massive effort is part of his Photo Ark project, what will ultimately be a 25-year odyssey to photograph every species living in human care, documenting the world’s biodiversity before it disappears. “It’s important for people to understand that as these animals go away, so will we,” says Sartore, who estimates that 50 percent of the creatures he shoots are on the brink of extinction. “This is the last chance they have to be heard before they go out of existence.”

He has now traveled to 50 countries and shot everything from a critically endangered black rhinoceros to a clouded leopard to the black and white spitting cobra. “You have to wear a face shield, so you don’t get venom spit into your eyes,” he says.

Because the animals were often born in captivity and cared for by humans, they are generally cooperative. “Chimps are the hardest, by far,” Sartore says. “I still don’t have a good picture of adult chimps, really. They’re smart, they’re fast, they’re strong, and they’re not afraid of anything.” Another challenge: giant manta rays. “I haven’t figured them out yet, but I’ve got plenty of stuff to do in the meantime,” he says.

With changes to the Endangered Species Act in August, which included weakening protections under the pretense of lifting regulatory burdens, Sartore’s work feels more urgent than ever.

“You can’t doom half of all biodiversity to extinction and not think that it will affect humanity,” he says.

John Gerrard

Using Computer Graphics to Visualize a New Era

YOU MAY NOT know it, but Spindletop, Texas, changed the world. It was the site of the first major oil find in the U.S., the Lucas Gusher, in 1901. It produced more oil in one day than the rest of the world’s oil fields combined. Its discovery is also credited for launching the modern petroleum age, leading to gasoline-fueled cars, oil for heating homes, petroleum plastics, and, yes, increased greenhouse gas emissions. Irish conceptual artist John Gerrard—whose work often focuses on computer-generated images and simulations—brought this pivotal site out of obscurity with his piece Western Flag. The CGI video, which debuted on a museum screen in 2017, transforms an oil derrick in Spindletop into a black smoke flag burning from a pole in the ground. The work has been brought to other locations via video screen installations, like the one in California’s Coachella Valley, above. “One of the greatest legacies of the 20th century is not just population explosion or better living standards but vastly raised carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere,” says Gerrard. “Here, a new flag attempts to give this invisible gas, this international risk, an image, a way to represent itself. I like to think of it as a flag for a new kind of world order.”

Justin Brice Guariglia

Bold Messages for a Warming Planet

THIS PAST Earth Day, April 22, a series of dire warnings came to the courtyard of Somerset House in London (above). Nine solar-powered roadwork signs displayed messages curated by artist Justin Brice Guariglia. The words were from poets, philosophers, and some of today’s strongest voices in the climate-change discussion—16-year-old Swedish activist Greta Thunberg and eco-theorist Timothy Morton, among others. “My show is meant to give us a language to rethink our relationship with the natural world,” says Guariglia. “The impact of our modern civilization is like an asteroid striking the planet.”

The New York City artist first got the idea to use roadwork signs while waiting outside NYC’s Holland Tunnel. He realized they were a great way to pass along a note of caution. “It’s hard to say if my work has any real influence over decision-making,” says Guariglia. “What I do know is that the work is getting people’s attention, and getting the public to think and talk about these extremely urgent issues, an important first step to solving these problems.”

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/32ZRxS2

No comments:

Post a Comment