Chris Maxwell seemed like any other Nigerian university student. He sat through lectures, most of the time with limited interest. He had a vibrant social life and many friends. But as one of three siblings, his parents, both civil servants, were stretched thin by putting even one child through university, let alone three. As costs piled up during his first year, Maxwell couldn’t afford necessities like rent, textbooks, or food.

“I just decided I needed to make money so that I can get some basic things for myself,” Maxwell, now 25, tells Men’s Journal.

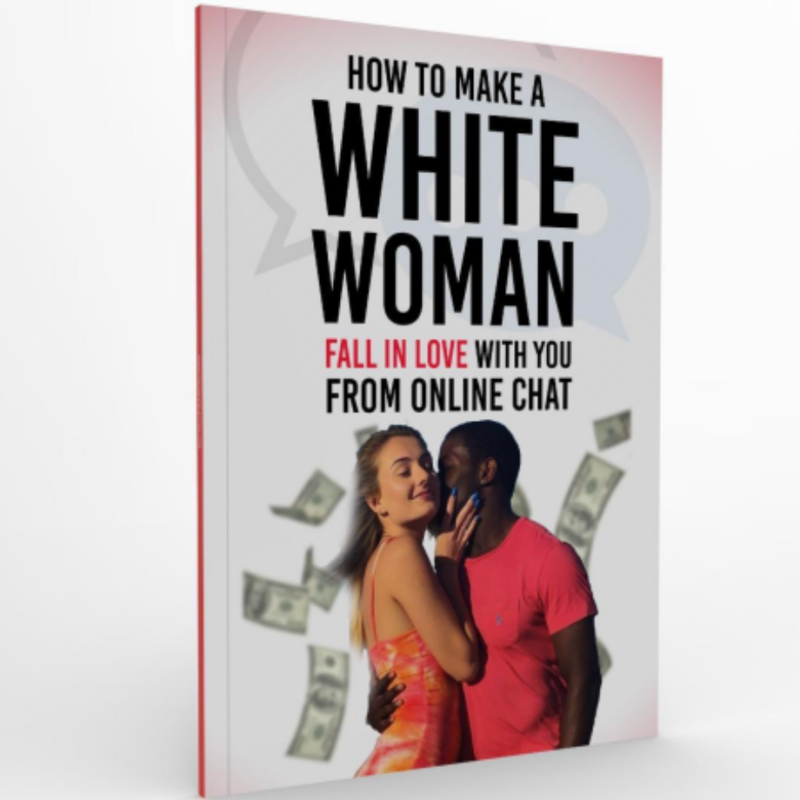

During his second year, he sought a job to help pay the bills. But instead of being a desk attendant at the campus gym or cashier at the university bookstore, he opted for a different and dangerous enterprise—one that was much more lucrative than typical college jobs and allowed him to work flexibly around his studies. With the help of a how-to guide he received from an acquaintance on WhatsApp, he concocted a fake online persona to romantically coerce middle-aged women out of tens of thousands of dollars.

Romance scams occur when a criminal uses a fake online persona to gain trust and emotional attachment from a victim. Scammers ultimately take advantage of the close relationship to steal money. In 2023, over 64,000 romance scams were reported to the Federal Trade Commission, costing victims a total of almost $1.14 billion.

Romance scams are illegal. In the eyes of the law, perpetrators are committing theft and fraud. But in Nigeria, there's a dearth of scammers, which a WIRED report attributes to unrest in the 1990s due to a jump in unemployment, lack of national social security, and rise of cybercafes providing widespread access to the internet. As the romance scam industry grew into the 21st century, scam operations began to act like semi-legitimate businesses, some decked out in offices with desktop computers and smartphones. Others, like Maxwell, act individually from their own devices.

For these scammers, the risk of fines and arrest is worth the reward. Nigerian GDP per capita, the economic metric that measures a country's economic output on a per person basis, is just $2,163 compared to the U.S.'s $76,330. And 133 million Nigerian people (more than half the population) are considered “multidimensionally poor," a United Nations Development Programme term that refers to lack of educational opportunity and basic societal infrastructure as well as money.

With the help of Nigerian police, international intelligence agencies such as Interpol and the FBI have cracked down on financial scams coming from Nigeria over the last decade. Last year, 60 Minutes Australia looked inside one crime syndicate, while Interpol's Operation Killer Bee took down another in 2022. But that hasn’t stopped this underground romance scamming industry from flourishing.

In most cases, romance scammers begin by stealing someone’s identity. At least 18 women claimed that British man Steve Bustin dated them due to a mass romance scam using his image. Army sergeant Stuart James, whose image had been used to scam people for over decade, has received hundreds of angry calls and texts from strangers. Criminals used New York City-based sports reporter Harry Cicna’s likeness in a Match.com scam, posing as army sergeants stationed in Afghanistan.

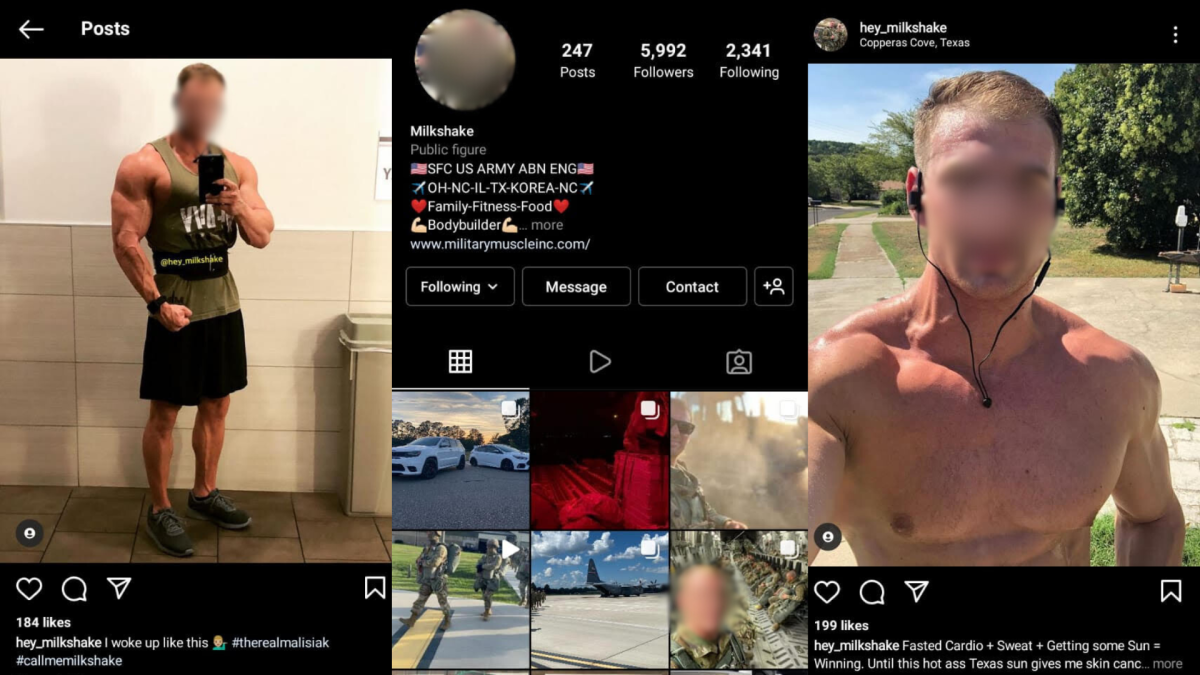

From his apartment, Maxwell donned the persona of a deployed army officer looking for love back home. Using a stolen image of a white blonde-haired bodybuilder with the handle ‘hey_milkshake,’ his persona acted out the typical life of a service member: moving base to base, from Illinois, Ohio, North Carolina, and Texas to Korea.

Courtesy Images

Using the playbook he received from an acquaintance titled How to Make a White Woman Fall in Love With You From an Online Chat, Maxwell followed step-by-step instructions on how to build trust and manipulate victims. Over 40 pages, riddled with spelling and punctuation errors (ironically, the section dedicated to grammar is misspelled ‘grammer’), the guide recommended he “... go for those over 40. They are working hence they have the money you need. Also, being single at 40, they are eager for love.”

Underneath sections titled ‘Bring Things Up’ and ‘Compliment Her,’ the playbook offers surprisingly solid conversational dating advice. But just a few pages later, innuendo takes center stage: “I’m jealous of your heart. ‘Cause it’s pumping inside you and I’m not.”

After months of trial and error, Maxwell finally found success, following the advice of the guide’s ‘Take Your Time’ section: “Spend days talking about random things, learn a lot about her. The more you know about her, the better it will be for you.”

“It's like a full-time job. It takes a lot of time. You need to be consistent and texting, constant conversation,” Maxwell says.

Courtesy Image

After building trust, scammers like Maxwell introduce an urgent need for money. An example reads: “Instead of asking her for money for mortgage. When she asks about your day you can tell her it was bad. Then tell her you are broke, you are behind [on] your mortgage, and they will kick you out next week, and you have exhausted every means to get money. By herself, she will offer to give you money.”

Over a few years, Maxwell successfully siphoned victims' money into his pockets. It wasn't solely for school expenses, however. He says he stole between $70,000 and $100,000 total from multiple women, upgrading his lifestyle with fancy clothes and lavish nights out.

But one victim, a woman in her late 50s, changed Maxwell. He approached her on Facebook before escalating their contact to daily conversations on Instagram and WhatsApp. For his victim, it seemed like a dream come true: A handsome, steady military boyfriend.

She was quick to help when Maxwell, as hey_milkshake, told her he lost his gun and needed money to buy a new one before his supervisors found out. She wired him increments of $800 to $1,000 through Western Union, or sometimes sent him Bitcoin or digital gift cards. She wasn't wary that they couldn't meet in person; after all, he was deployed, and wouldn't receive leave time for years.

But when her losses piled up to $15,000, with no timeline when she would see her mysterious online boyfriend, she began to feel skeptical. She contacted Social Catfish, a small, California-based tech company that verifies identities through a combination of reverse image searching and background checks to help law enforcement agencies bust scammers. Her suspicions were correct; she'd been scammed.

Seeking justice, Social Catfish connected her with Nigerian authorities, who found his location by reverse image searching the pictures on hey_milkshake's Instagram page, pinpointing Maxwell’s IP address. They discovered that a common location from where the fraudulent images were uploaded—a computer at Maxwell's residence and a phone registered in his name, leading authorities right to his apartment.

They busted down his apartment door to apprehend him and called the victim, handing Maxwell the phone. He revealed himself on video, ending the facade, while she sobbed on the other end of the line. In that moment—the veil of his fake identity torn away in real time—Maxwell finally realized the consequences of his actions.

Andy Hirschfeld

In most situations, scammers pay a fine, and that’s the end of the case. But after paying an undisclosed amount, Maxwell's renounced scamming for good, intending to change his life. But he was just one small fish in a very big, very shady pond.

A recent study in the Journal of Economic Criminology spoke with 10 victims of Nigerian romance scams, all middle-aged women, revealing the psychological trauma underpinning their cases. One victim said they felt intense love for her scammer because he feigned emotional care she never received from exes.

“He was fully involved and often showed interest in my affairs,” she told researchers. “I have two daughters, and he will spend long hours asking and talking about them. Something that their fathers don’t bother to do.”

Three victims even admitted to discussing marriage with their scammer, while all of them experienced “... sexual abuse through cybersex,” says the study.

Ultimately, once the scams were revealed to them, the victims experienced severe physical and emotional consequences, including heavy alcohol and drug consumption, unhealthy eating, poor hygiene, sleeplessness, and depression. According to the study, some of the victims sought the help of doctors and psychologists to recover.

To handle their emotional pain, the women fought back. Seven took legal action against their scammers. Five even flew to Nigeria to testify at the criminal trials against their scammers. While it doesn’t erase the abuse or return dollars to their bank accounts, most of the women believe the fight has eased their trauma.

“I needed to fight him legally and get his memories off my mind in the process,” said one victim. “That way I won’t have any emotional attachment towards him.”

It’s not just middle-aged women that scammers victimize, however; Maxwell says to be wary of anyone who posts limited personal details on their social media profiles or asks for financial help via gift cards, cryptocurrency, or cash. And although a 2022 AARP survey found that 53 percent of the public identifies victims as “culpable and blameworthy” for being scammed, Gallup research from last year states that “no subgroup of Americans is exempt from being scammed” (though the rate is higher among vulnerable populations like low-income households). The study found 15 percent of U.S. adults say that at least one member of their household has been scammed before.

Fueled by remorse, Maxwell reached out to Social Catfish—the organization that took him down—for a job. On paper, he's a contracted consultant. But in reality, he's a private investigator and criminal informant that performs reconnaissance and reports back to the company so authorities can take action. Likening it to the plot of Catch Me If You Can starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Tom Hanks, Maxwell travels across Nigeria to meet suspected scammers in person, verifying their addresses and identities while disguising his own.

Maxwell hopes he's making a difference (due to ongoing criminal investigations, Social Catfish declined to offer specifics). Because he knows that until such operations are dismantled for good, scammers' pockets will be lined with the money of innocent victims—leaving psychological trauma in their wake.

Related: Study Finds Most Tinder Users Are Already in a Relationship

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/n0oYwT2

No comments:

Post a Comment