After a week of heavy fighting against Ukrainian forces in and around Bucha, the Russian military captured the strategic town on the outskirts of Ukrainian capital Kyiv on March 4, 2022. The next day, another cadre of uniformed invaders arrived, older than the typical teenage Russian conscripts, and the noncombat killings began in earnest. It was obvious to besieged locals that these were not regular soldiers. They appeared to act autonomously, and more viciously.

At first, the bloodshed was indiscriminate. A middle-aged man riding his bicycle was shot in the back for sport, a woman returning from the grocery was cut down by a burst of automatic fire. Unarmed residents were robbed at checkpoints and then murdered. Gunfire was heard at all hours, as were the screams. Bodies were left where they fell as warnings. Soon, the carnage grew even more sadistic, and systematic. Survivors recall how these “soldiers” raided apartment blocks to round up males under 50 years of age, and then bound and executed them. Women were raped and tortured as the armed men laughed and drank. Some corpses were set on fire. Bucha residents, at great peril to themselves, dug hasty graves for other victims, their friends and neighbors, when the Russians weren’t watching.

When Ukrainian forces liberated Bucha on April 1, they entered a ghost town littered with rubble and smoldering vehicles. The dead were everywhere. Bodies were strewn for half a mile along Yablosnka Street in the southern part of town. By conservative estimates, more than 400 men, women and children had been murdered.

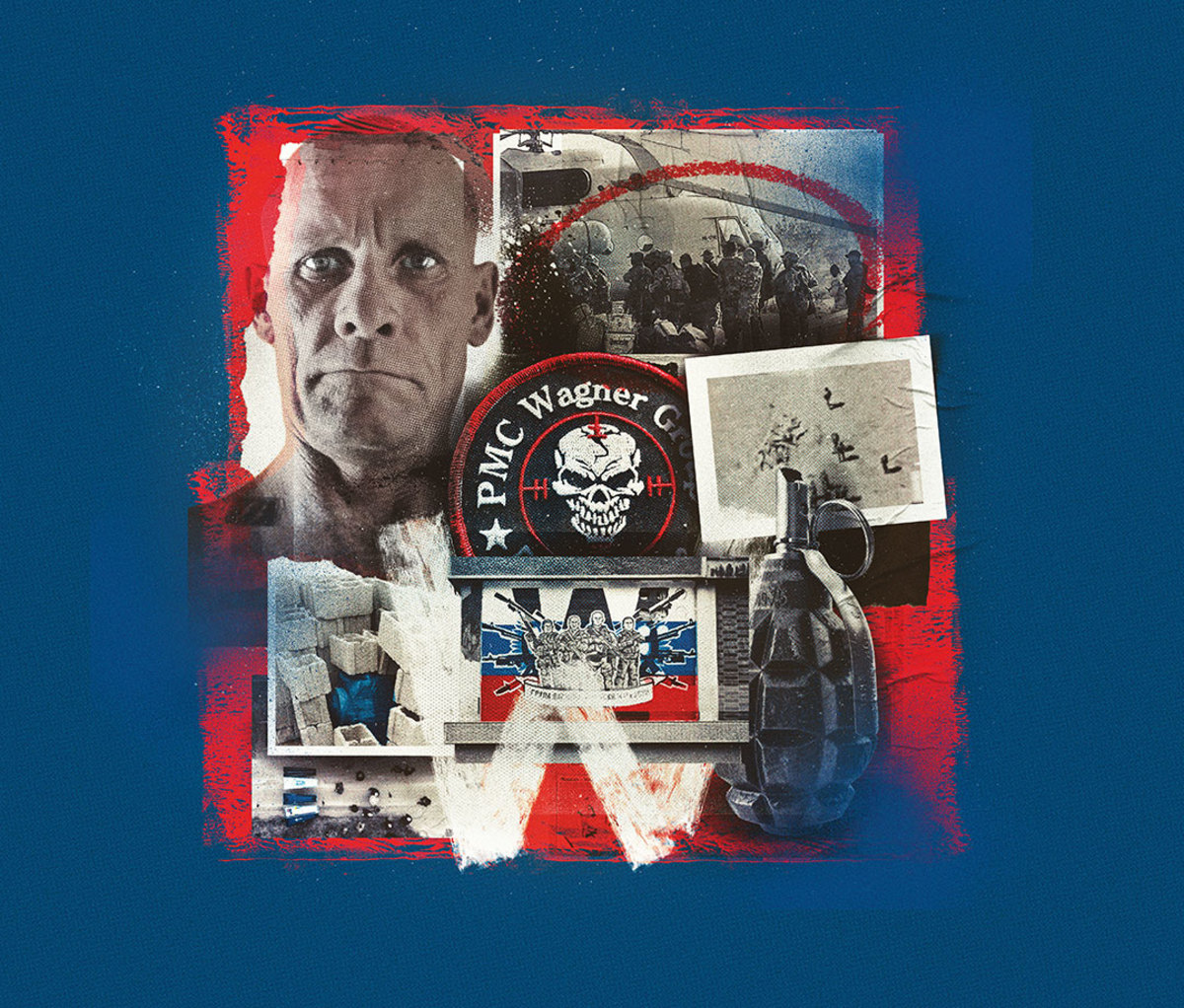

That massacre is yet another landmark of horror perpetrated by the notorious Wagner Group, a mercenary organization serving Moscow’s global sphere of influence—from the steppes of Ukraine to the deserts of Syria to the killing fields of Africa. Mysterious and ruthless, the Wagner Group has become a much-feared arm of the Russian regime. And those with knowledge of Kremlin machinations know they function as Putin’s private army.

Russian oligarch Yevgeny Viktorovich Prigozhin, 61, is widely believed to be the owner of the business enterprise that is the Wagner Group. Born in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), the eruptive Prigozhin grew up a streetwise student of the Soviet Union’s rampant corruption. He spent nine years in prison for theft and robbery before being released into the tumultuous pivot of Russian history when the Iron Curtain crumbled from communism to nepotistic capitalism. The Soviet penal system provided a master’s degree for opportunists who were savvy and ruthless enough to stake their claim amid the chaos.

Starting with little, Prigozhin amassed a fortune. He grew a humble hot dog business into a supermarket franchise, and used the proceeds to buy casinos. His St. Petersburg restaurant, The New Island, was a favorite of the city’s rich and notorious—including many former KGB officers. One of his VIPs was rising political star Vladimir Putin. Prigozhin became known as “Putin’s chef,” and with his shaved head and $5,000 suits, looked like a Hollywood stereotype of a Russian henchman.

When Putin assumed power in 2000, the country’s spoils were divvied among such men, who adhered to a simple rule: As long as Putin is in power, this new breed of oligarchs are allowed to rake in untold fortunes, but their survival hangs by a thin wire of absolute loyalty—and financial servitude—to the

Russian president.

Prigozhin was handed lucrative catering contracts for the nation’s schools and military. Those contracts made him a billionaire, and he used the profits to launch even more businesses, including firms specializing in information, such as Internet Research Agency, a nefarious troll farm of some of the most capable Russian hackers. (Well before punishments were leveled at Russia for invading Ukraine, he was already under numerous sanctions by the U.S. Treasury Department for cyber interference in the 2016 U.S. elections.)

In 2014, two years into Putin’s third term as Russian president, Prigozhin invested in a shadowy mercenary firm founded by Dmitry Utkin, a neo-Nazi and former GRU (Russian military intelligence) officer who idolizes Adolph Hitler. Utkin is a veteran of two bloody wars against separatists in Chechnya—including house-to-house battles in Grozny—and commanded a Spetsnaz commando formation. He left in 2013 as a lieutenant colonel, but did not spend his retirement fishing. He went to work as an enforcer-for-hire for Slavonic Corps, a Russian private security company contracted by Syrian president Bashar al-Assad’s regime to recapture oil fields seized by ISIS and punish enemies in that country’s ugly civil war. Utkin’s radio call sign was “Wagner,” a reference to Hitler’s favorite composer. (Ironic, given Putin’s flimsy “denazification” rationale for invading Ukraine.)

Prigozhin’s deep pockets lent stature to Utkin’s private-army enterprise, and, with Putin’s approval, it became Private Military Company Wagner.

Though Slavonic Corps was registered in Hong Kong, there are no official corporate records for the Wagner Group. Foreign Policy wrote, “[Wagner] has become a shorthand, bound up in mythology, [a] network of companies and groups of mercenaries that Western governments regard to be closely enmeshed with the Russian state.” In fact, according to Marc Polymeropoulos, a retired clandestine officer and author of Clarity in Crisis: Leadership Lessons from the CIA, “the Wagner Group is the paramilitary arm of Russian military intelligence.” In other words, they are the contractors and subcontractors of Putin’s will.

Mercenaries actually are outlawed under Russian law, but companies specializing in trigger pullers willing to risk their lives and commit atrocities for big paydays are an open secret. They’re deemed necessary to protect criminal territories and businesses controlled by the oligarchs who serve Putin’s interests. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the Wagner Group follows the trend of the “privatization of state violence” in Russia.

At first, like the Western private military companies that emerged during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (think: Blackwater), the Wagner Group hired elite-unit veterans with combat experience who were paid as much as $3,700 a month—CEO money in Russia—to put their skills to ruthlessness ends. Further tying the knot to the Kremlin, the Russian Ministry of Defense provided Wagner with part of a GRU and special-forces base in the town of Molkino in southern Russia. The base includes barracks, shooting ranges and other installations needed to prepare an army for war. The GRU also provided Wagner with assault rifles and rocket-propelled grenades. Those trained at the base ranged from seasoned combat veterans to wannabes who had never fired a weapon before.

According to a Wagner fighter interviewed by the BBC, there are three types of people attracted to joining the group. The first is the classic soldier of fortune, someone who craves adventure, combat pay, heavy drinking and fast women. The second is the lost soul resigned to the realization that fighting and killing is the only conceivable way he can earn a living. And the last category is what the operator termed the “romantic,” people who are determined to serve their country and in the process get a jolt of adrenaline and a paycheck.

Interviewed in silhouette by Britain’s Sky News, a former Wagner operative named “Alexander” said, “The training was quite intense. We were taught how to aim, use arms, artillery, rifles, missiles, tanks and APCs.” Alexander had no military experience before entering the gates of the Molkino camp. He received a bonus of 250,000 rubles (about $4,000) as an incentive to stay on. A trigger puller, even a green rookie, could earn as much as $16,000 for a three-month tour—approximately a full year’s average salary in Russia.

Wagner units were first noticed in 2014 in eastern Ukraine. The hired mercenaries joined Russian conventional forces and their separatist allies in the annexation of Crimea, and then terrorized civilians in the Donbas region, committing acts of murder and pillage designed to intimidate Ukrainian soldiers and civilians into surrender. The Ukrainians dubbed this new threat “the little green men.”

A reputation for brutality became a marketing bonanza. Wagner’s services were soon in demand in the Middle East, most notably in the internecine slaughter of the Syrian civil war to support Russian-backed President Bashar al-Assad. According to intelligence estimates, the Wagner Group assembled close to 5,000 soldiers of fortune for Syria. They arrived in August 2015 aboard the same Antonov and Ilyushin transport aircraft as regular Russian forces, touching down at the sprawling Khmeimim Air Base near the Latakia coast. The military bombed anti-government targets, then Wagner fighters participated in clearing Syria’s cities in house-to-house fighting, dirty work requiring heavy hands, brutal tactics and plausible deniability. Civilians were frequently caught in the crossfire, and sometimes made examples of. The bodies of those killed were left in the desert or cremated; families received payouts to avoid political fallout.

Syria was a windfall for Prigozhin. He cut lucrative energy contracts with the Assad regime, earning a whopping 25 percent stake in Syrian oil fields liberated and protected by his men. Tribute, of course, was kicked up to Putin’s secret bank accounts. “Mike,” a Kurdish liaison officer with U.S. and coalition units in Iraq and Syria, once commented, “The Russians were nothing more than bandits, seeing what they could steal and not letting anything get in their way. Soldiers do not kill women and children, they do not steal. Only criminals do that.”

Human rights groups also took notice of Wagner and accused its personnel of perpetrating war crimes wherever they were deployed. But for Putin’s purposes, the mercenaries were deniable and cost effective.

The Wagner Group does not employ a public affairs officer to elaborate on its missions. Its employees are forbidden from giving interviews. As such, the Kremlin can always issue a boilerplate shrug that it had no knowledge of their presence in a war zone. But most believe that there exists no daylight between Wagner and the Kremlin. John Sipher, a 28-year veteran of the CIA’s National Clandestine Service, says, “The Wagner Group’s operations are designed to provide Moscow with plausible deniability, but the opposite is true. They work closely with the GRU, the SVR foreign espionage service and the FSB, the post-Soviet KGB. They are irrefutable organs of the Russian state. Their deniability is purely implausible.”

Wagner puts boots on the ground wherever natural resources and pro-Putin regimes with tenuous security situations need extra tactical muscle. Wagner units fought government forces in Libya. They deployed to the Central African Republic, Sudan and Madagascar. Wagner even has been detected in the Americas, in oil-rich Venezuela, supporting the narco-regime of President Nicolás Maduro. Wherever they are sent, civilians are tortured, raped and murdered. Moscow denies, but in the age of smartphones, hard evidence that Russian nationals are implicated in horrific atrocities is impossible to mask.

So, too, was the only conventional battle that has occurred between Wagner operatives and the U.S. military. On Feb. 7, 2018, approximately 600 Wagner fighters, supported by tanks and artillery, attacked a Syrian Democratic Forces position near Deir Ez-Zor in the eastern stretch of the desert near the Iraqi frontier. The SDF contingent, mainly Kurdish fighters, was bolstered by elements of the U.S. Joint Special Operations Command, including operators from Delta. AC-130 gunships unleashed airborne fire support from thousands of feet above the desert to assist the Americans and Kurds. What was not obliterated by air was left for the Delta operators to sort out on the ground. More than 300 Wagner Group fighters reportedly were killed in the lopsided battle. U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis would tell Congress, “I ordered their annihilation.”

Russia’s state-controlled media made no mention of the engagement, of course. Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov dismissed the reports as “fake news.” The nameless mercenaries were left to rot where they were killed. There were no military funerals, only small payouts delivered to their next of kin, as per their contracts.

The myth of the Wagner fighter as some sort of Russian Rambo was debunked in the Syrian desert that day. “Killing women and children was a lot easier than fighting a disciplined and capable military opponent,” says Polymeropoulos. “But owning a reputation for killing civilians is precisely why we see Wagner mercenaries in Ukraine today. Their presence alongside Russian conscript forces is designed to terrorize an occupied population.”

Putin likely hoped that his proxy private army would not be needed in Ukraine at all. Moscow designed the war to be fast, furious and finished before the West could respond. The massive Russian blitzkrieg would overwhelm Ukraine’s military, murder President Volodymyr Zelensky and install and a pro-Putin puppet regime in Kyiv. Putin’s generals assessed that the Ukrainian capital would be seized within three days and the country pacified within a week. The Pentagon, in congressional testimony offered by Defense Intelligence Agency director Lieutenant General Scott Berrier, concurred.

But best-laid plans did not calculate the furious defiance of the Ukrainian people and Zelensky becoming a modern Winston Churchill. Putin also misjudged NATO’s resolve. Russia’s conscript army was soon stalled, and forced to lay siege to a nation of more than 40 million inhabitants. It’s Russia’s way of war: Unleash overwhelming firepower that has little regard for international law and civilian casualties, and if that fails, deploy a more covert attack that, as John le Carré once wrote, “obliterates, punishes and discourages.” It is a scenario tailor-made for the Wagner Group.

Wagner mercenaries were first deployed to the separatist enclaves of Donetsk and Luhansk to help crush the will of the pro-Ukrainian population. But as the initial Russian offensive stuttered into a quagmire, heavily armed men sporting Wagner patches were sent in to join—and lead—the military effort elsewhere. They were not only ruthless—always an effective tactic in beating down an occupied population—they were more dependable than the green Russian troops thrust into a conflict they did not want or understand.

A significant number of the armed men on Wagner’s payroll are Serbs, a Slavic ethnic group with a long history of executing wars of ethnic and religious butchery. Murals have appeared in Belgrade applauding the actions of Wagner fighters in Ukraine. But Wagner leaders also pulled personnel from other global hot spots and summoned violence-tested veterans. Chechens arrived on the battlefield, as did Libyans and Africans—a cheaper alternative to the Russian soldiers of fortune.

The Wall Street Journal reported that the Bundesnachrichtendienst, Germany’s foreign intelligence service, intercepted secret electronic communications between Wagner Group operatives solidifying what NATO espionage services already suspected: Russian mercenaries played a dominant role in the Bucha massacre.

But just a few days into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, another Wagner Group cadre also was still hard at work in Africa, propping up Mali’s military junta leader, who is reliably pro-Moscow and can protect Russia’s interests in the resource-rich region. On March 27, the mercenaries entered Moura, a rural hamlet that was not playing along. Some arrived on trucks and others were choppered in via military helicopters. They advanced quickly through the dirt streets, raiding the mosque in search of Islamic insurgents, pulling men from their homes. Those unlucky enough to be captured were beaten, bound and marched four miles to the banks of the Niger River. By the time the mercenaries left four days later, more than 300 corpses lay rotting in the muddy water. Nearly all of the dead were civilians.

Prigozhin and Utkin already have been sanctioned by the European Union for their Wagner roles. There is talk in Congress and in the E.U. of classifying the Wagner Group as a designated terrorist organization, a legal move that would allow nations greater leeway in bringing members to justice. To that end, U.S. and other NATO intelligence services are already gathering evidence to prosecute Russian soldiers—and soldiers-for-hire—in war-crime tribunals that most certainly will follow the eventual cessation of hostilities in Ukraine. No doubt some of that bloody account of atrocities will be laid at the feet of Wagner Group fighters. Hopefully, the charges also will extend to their paymasters, even at the highest level.

Samuel M. Katz has written more than 20 books on counterterrorism and special operations. His latest, No Shadows in the Desert, covers the spies who carried out the secret espionage campaign to eliminate the heads of ISIS.

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/GBOk03j

No comments:

Post a Comment