The first morning on safari, our small expedition treks 10 miles along a creek, across Kenya’s Lewa Wildlife Conservancy. First managed in the 1920s as an immense, colonial ranch, Lewa was converted in the 1960s to a refuge for the last remaining rhinos of Northern Kenya. When cattle moved out, wildlife thrived. Now thick with elephants, rhinos, lions and leopards, it’s a gateway to one of the last true stretches of accessible wilderness left in Kenya.

Our ultimate goal is elephant habitat, but this early on we’re content to pass dazzles of Grévy’s zebra mixed in with reticulated giraffes and bachelor groups of Thomson’s gazelle. Lesser kudus scale cliff embankments above us. We’re enthralled by the tranquility of walking in nature, constantly scanning for Cape buffalo that could burst from thickets with a snorting charge, or for aggressive black rhinos shading under trees.

We’re so occupied looking for the big things, we nearly miss one of the smaller, more dangerous things right under our noses. Tucked up under a fallen tree across our path, a puff adder coils. It is so well camouflaged that our two expert guides pass within inches. Then my 16-year-old son, Landry, spots the snake’s flickering tongue and freezes his foot mid-stride. Puff adders are lazy but strike with lightning quickness when disturbed. Their venom can be fatal, and this one is six feet long and fat as a stuffed hockey sock. Landry leaps back, and remembering that it’s important to look where you step in the African bush, we gave the adder a wide berth.

We set up camp that afternoon under a sweep of acacia trees beside the Ngare Ndare River. We eat a lunch of curry chicken pie, followed by downtime in our tents to wait out the day’s most intense heat. Affectionately known as “meat sacks,” the tents are made of meshed netting to catch any breeze, and so that you can look out from inside.

Around 4:30 p.m., we emerge for a cup of chai, then walk out without the camels just to see what we can before sunset. We head up a tributary and soon startle a pack of hyenas just emerging from their den for an evening hunt. Their anxious yipping rouses a buffalo wallowed down in the grass, and it rises menacingly just ahead of us. If it hadn’t been for the hyenas, we would have stumbled right into him. For the second time that day, we luck into a narrow escape. Maybe my uncle Peter is looking out for us.

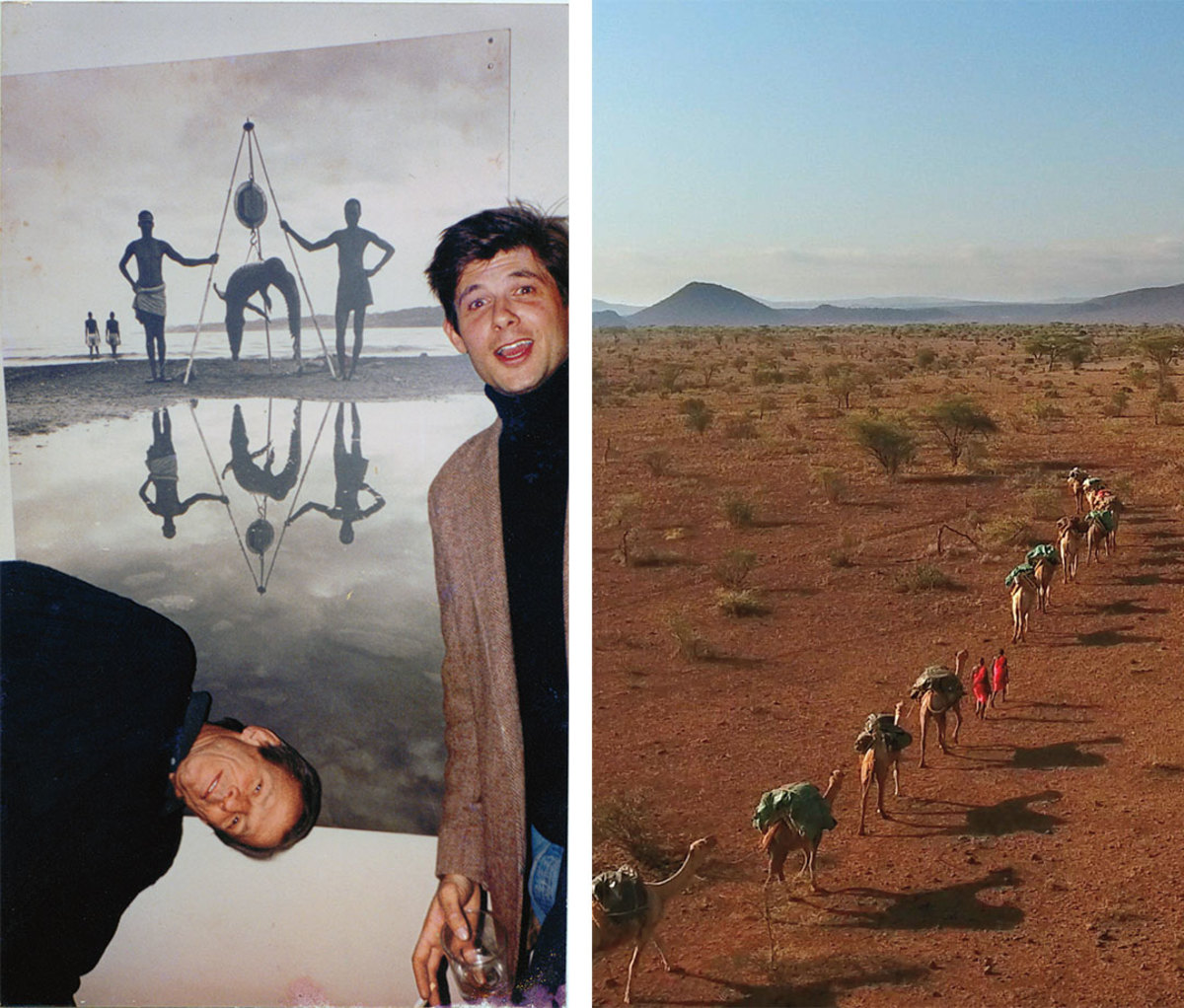

On April Fools’ Day, 2020, just a few weeks into the pandemic, I learned that my uncle Peter Beard, the renowned photographer and artist, had wandered off into the woods in Montauk at the East End of Long Island, New York. People turned out in droves to search for him, but like an old warthog that wants to rest in peace, he’d limped off and vanished.

Weeks passed, and with the weather frigid, it seemed increasingly unlikely we’d ever see him again. Peter, 82, had suffered a few strokes over the previous years, and a bit of dementia had set in. Still, without a body, speculation filled the void. Some thought he’d gone to the cliffs overlooking the ocean and plunged to his death, either accidentally or on purpose. Others said he’d simply hopped in someone’s car and was off on a bender.

After all, Peter was an infamous maverick. Friends with Andy Warhol, Truman Capote, Mick Jagger, and Jackie Onassis, he’d been married to Cheryl Tiegs and discovered another supermodel, Iman. He also had an intense passion for Africa, where he’d survived lion charges, crocodile attacks and, most notably, an elephant mauling. If anyone could just reappear with a shrug and a cat-that-ate-the-canary grin, it would be Peter.

The spring thaw ended such hopes. A hiker found what was left of my uncle in a ditch. Apparently, he’d gotten lost and died of exposure. It was said to have been an appropriate end, out in nature, but I wished he’d never been found. To just leave everyone guessing, like he was Amelia Earhart or D.B. Cooper, would have been more fitting.

Due to Covid, there wasn’t the sort of public send-off one might expect for someone of his stature. Instead, there was a small, socially distant burial in a cold rain at a family plot in Southampton. Locked down at my own home in New Orleans, I couldn’t attend, and didn’t really want to. It seemed too gray a ceremony for someone so colorful.

Instead, I hatched a plan I thought Peter would approve. As soon as travel restrictions allowed, I’d fly to Kenya to sleep under the stars, search for elephants on foot and say goodbye with a glass of whiskey by the fire.

My association with Peter and his vision is among my earliest memories. When I was a little kid and called him Uncle Pizza, I’d listen to his safari tales while he crashed on our couch and doodled on photos of wildlife inside copious journals. This was before he was famous for being infamous, still then best known as the author and photographer of The End of the Game and Eyelids of Morning, both prescient portrayals of the decimation of Africa’s wilderness.

Peter took me to Africa for the first time in the mid-1980s, when I was 16 years old. I spent the summer at Hog Ranch, his tented camp outside Nairobi, and from there joined an expedition with explorer Quentin Keynes, who was Charles Darwin’s great-grandson. Keynes had first brought my uncle to Africa in 1955, when Peter himself had been 16. For me, it was the beginning of many such trips, and also the start of my life as an artist, a conservationist and a lover of places with more animals than people.

Now my own son is 16, and in turn has grown up listening to me tell stories of my and his great-uncle’s travels, in a house full of Peter’s photographs and my own paintings. Symmetry suggested it was a good idea for Landry to come along.

And so, a little more than a year after Peter’s funeral, my son and I land in Nairobi before dawn and meet our driver.

As we motor along, I look out the window at the sleeping city, amazed at the scale. Man’s footprint is always growing.

When my uncle first came here, 200,000 people lived in Nairobi. When I was a teen, it was fewer than a million. Now there are 5 million. In his later, more cynical years, Peter railed against what he called “the galloping rot” of human sprawl, but I’m a little more sanguine about the inevitability of the modern world. I try to appreciate what there is, instead of lamenting only what used to be.

We drive north across the equator and skirt past Mount Kenya and on to Lewa, a landscape that cascades off the northern slopes of the mountain in descending plateaus, from cool green forests to arid acacia woodlands, and down into the hot, dry scrub of Kenya’s Northern Rangelands.

Just beyond the conservancy, control of the land passes into tribal hands, where there are no fences, and other than the Il Ngwesi and Mokogodo tribes, very few people. Along the banks of the Ngare Ndare, in a tangled woodland of acacia, fig and boscia trees, a density of wildlife hides in thorny cover. And in June and July, when the tortillas acacia trees drop seedpods, elephants converge from all over the north to gorge themselves and frolic in the dappled shade.

To get there, we need a guide. Charlie Wheeler is an old friend, a third-generation Kenyan farmer who lives at the edge of the Ngare Ndare Forest, a World Heritage Site that he manages. Now in his late 60s, Charlie has spent a lifetime in the bush. As a young man, he traversed Northern Kenya, wrangling the few critically endangered black rhinos that hadn’t been poached and relocating them to Lewa. Between then and now, he’s traipsed across much of this landscape. I’ve heard him called an “elephant whisperer,” and the Samburu people named him Lakitalan, he who walks out and comes back with stories. We’ve been on many walking safaris together, and when I told him of my intentions to go out with Landry to bid farewell to my uncle, he agreed to outfit the expedition.

When we arrive at a Lewa stream crossing, Charlie is waiting at the head of a train of camels. Though perhaps not typically associated with safari culture, camels have been a reliable means of transport in Kenya for centuries. Herded down from Somalia and Ethiopia, they’re common across the dry north, and we need them for the sort of trek we’re undertaking. Camp equipment—tents, bedrolls, tables, chairs, canvas bush showers, snakebite kits, kitchen supplies, water, food, personal baggage and, in my case, art supplies—all have to be hauled. The camels will bear our gear while we walk beside.

To man the journey, Charlie brings his crew, drawn from tribes across Northern Kenya. Two women, a Meru and a Boran, run the camp kitchen, while two Turkhana and one Maasai are tasked with setting up the campsites. A Ndrobo hunter-gatherer named Saluna, who moves through the bush like a gazelle runs, acts as a scout, and a pair of brothers from the Kaisut Desert handle the camels. One of those brothers is called California after a bar in Kenyan Somaliland where he can often be found when he’s not out on walkabout. He’s what might be thought of as a witch doctor, but he prefers the term wizard. He’s kind and slight, but if crossed, will spit in a circle and utter a convincing curse.

The final member of the crew is a Rendille tracker named Letaruga, who can identify and follow just about anything, anywhere with no more of a clue than a few scuffs in the dust.

Only Letaruga and Charlie are armed. Charlie carries a heavy, bolt-action .458-caliber Westley Richards rifle, a bequest from an old game warden, and Letaruga shoulders a 12-gauge pump-action riot gun with slugs the size of your thumb. The goal is never to use either weapon, but where we’re going, it pays to be prepared for what might come charging out of the bush.

Eager to get going, we load our gear onto a droopy-lipped Somali camel, and set off on foot into the wild.

After that first day’s encounters with the adder and the hyenas, we shower under buckets of river water. Around the campfire we discuss the state of the world, and thank the stars to be beyond the daily news cycle of politics, wildfires and disease.

Over the next days, we settle into a routine. We wake at first light, listening to the dawn chorus of birds. We eat oatmeal with fruit and local honey, then strike camp. We walk between five and 10 miles to our next campsite, searching along the way for wildlife. In the afternoons we rest, then set out again before twilight to look for elephants.

It’s a very different experience than driving through a game park. The animals are much more skittish or dangerous, depending on the circumstances. You have to pay closer attention and be more deliberate in your movements. And often, when you go out looking for one thing, you bump into something else.

A few days into our safari, now passing through Il Ngwesi tribal land, we follow the trail of a big elephant along the river. We hear a thrashing in the bushes, and what we presume to be the elephant turns out to be a pair of mating lions. The male growls at us before retreating. We figure it will be the last we see of them, but for the next few days they are very much present. They roar around our campsites, and while at first we think it’s just the two, it becomes apparent that we’ve been joined by a whole pride. We double the guard around the camels and fall asleep to the moaning of lions just outside our tents. Uncle Peter would have loved it.

Three more days upriver brings us to a spot called Campiya Chui, the camp of the leopard. This is the honey pot, surrounded by a forest into which elephants come in their droves. At the campsite, a 500-year-old boscia tree stands alone in a clearing. Its bark shines silver in the moonlight. The Samburu people think the tree is haunted, that the ghosts of ancestors live in its branches. Passing warriors stab the trunk with their spears to keep the spirits at bay.

We’d spotted a few elephants in previous days, but the conditions had always been a little off to get close. Either the breeze would give us away, or light was fading and we didn’t have time to position ourselves correctly. Today, however, everything lines up. Letaruga finds the tracks of a family herd that had lumbered past camp earlier that morning, and we follow the trail, periodically kicking dust to check the breeze. As we go, the dung gets fresher, and I detect the scent of elephants in the air. The forest feels awake in a way that it doesn’t when elephants aren’t in it, like the trees might come alive around you. And then we’re upon them—elephants are everywhere, in front of and beside us, walking across our path. We tuck in beside an acacia tree and spend a glorious afternoon among the herd.

We return to camp elated. To celebrate properly, California buys a goat from a passing herdsman. Saluna slits its throat and drinks its warm blood before butchering the carcass in the grass. We roast the meat over the fire, and the whole crew digs in heartily.

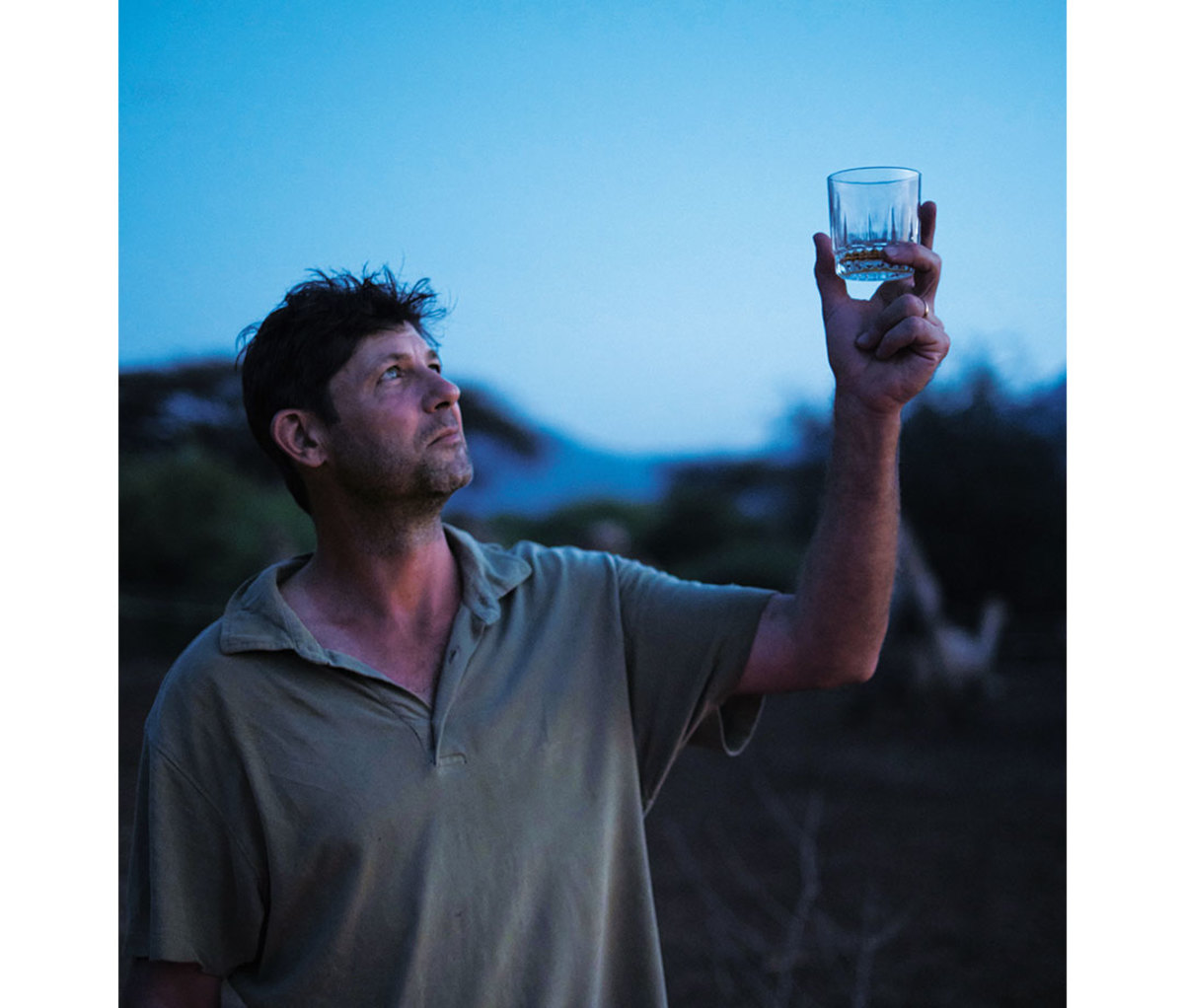

After dinner, with lions still roaring in the dark, I break out a bottle of Writers’ Tears, an Irish copper pot whiskey I’d brought along for the occasion. I pour two fingers into each of our glasses.

“To Peter,” I say, “and to big tuskers and great adventure.” We toast, raising our drinks to the stars.

I look over at my son in the firelight, and at my friend Charlie. I think about the elephant matriarchs we’d seen that afternoon on guard with their little ones beside them, and I’m aware of a kind of continuity in which generations of elephants, and generations of my own family, and the age of the tree we stand beneath, come together. And I consider how important it is to keep places like this healthy and intact, so that my son’s son can experience the same. And I think about Peter, and we drink well into the night, telling stories of his escapades. Then, having properly said goodbye, I stab the tree trunk to keep the spirits at bay.

THE WATERING HOLE FOUNDATION

Founded by this story’s author, Alex Beard, in 2012, the Watering Hole Foundation is dedicated to saving endangered wildlife and preserving the Earth’s remaining wilderness. By identifying local initiatives that are actively striving to preserve the natural environment and its inhabitants, the foundation spreads awareness of these conservation efforts, raises funds to help these initiatives succeed and leads potential supporters on trips to experience the natural world firsthand. To find out how you can get involved, make a charitable donation or inquire about participating in future conservation walking safaris, please visit wateringholefoundation.org.

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/s6pzfjv

No comments:

Post a Comment