The American pact with its wide-open spaces seems simple enough: This land is your land, this land is my land. Such a noble ideal, in reality, is anything but simple to manage. However you weigh the value of public and private interests, recreation and industry, preservation and progress, we all can recognize that once wild lands are lost, they are not likely to return. It’s easy to say that our country’s natural wonders deserve protection. Meet the men on the front line, actually doing the hard work. These eight public land defenders have chosen paths that put them squarely in the fight, and often squarely in the path of real danger. As defenders who battle wildfires or track wild horses, expose polluters or face down injustice, that loss of nature is not an option.

The Riverkeeper: Kemp Burdette

The key to catching alligators is patience and solid core strength. At least, that’s how Kemp Burdette tells it. “They’re pissed when you hook them, rolling and running, but they don’t have a lot of stamina,” he says, describing how he brought in an 11-foot gator with a deep-sea fishing rig on the edge of North Carolina’s Cape Fear River—wearing it out, then slowly dragging it in.

As Cape Fear River Watch’s full-time Riverkeeper, Burdette and a team of NC State scientists were on the clock, holding down the primordial beast so they could test it for traces of chemicals discharged upstream. Such risks aren’t new to the former Navy rescue swimmer and Peace Corps volunteer who returned to his home state to try to clean up “the Fear.”

The 9,000-square-mile river system provides drinking water to 1 in 5 North Carolinians and hosts wildlife that also includes pelicans and manatees, but is plagued by a massive chemical facility, coal-fired power plants and the largest pig slaughterhouse in the world.

Most days, Burdette kayaks the Fear or its tributaries, taking water samples. Other days, he’s navigating waves of coal ash as they flood into the river, or he’s in a small airplane, flying above farms to look for improper waste disposal.

In the last decade, Burdette has helped remove coal ash ponds from public lands, forced DuPont to stop dumping chemicals, and worked tirelessly to reduce the impact of the swine and poultry industry that operates largely unchecked on the river’s banks—a job with no finish line in sight. “I love it here,” says Burdette, “but this river needs help.” — Graham Averill

The Ice Man: Will Gadd

Will Gadd has scored plenty of personal bests in myriad adventure pursuits—first descents as a pro kayaker, two world records as a pro paraglider, three X Games golds and the first ascent of a frozen Niagara Falls as an ice climber.

Recently, though, Gadd has applied his prodigious skills to the greater good for public lands, working with scientists studying the impact of climate change. He has helped researchers explore caves beneath Canada’s Athabasca Glacier, an endeavor that discovered a new life-form (a biofilm on the cave walls). And he has climbed below the Greenland Ice Sheet with scientists to learn how ice melt might impact sea levels.

“As an athlete, a lot of what we do isn’t useful,” says 53-year-old Gadd. “I feel like I can be genuinely useful to these scientists in these harsh environments, helping them move around and conduct research.”

Gadd understands that climate change often can be an abstract. For ice climbers, it’s a harsh reality wreaking havoc on renowned destinations. Take Mount Kilimanjaro: Since 1912, roughly 90 percent of the glacier atop Africa’s highest peak has melted. In 2014, Gadd climbed Kilimanjaro’s ice fins, vertical slabs of isolated ice jutting from the sand. He returned in 2020 to reclimb those same fins, rebuild a weather station with a climate scientist and bag the last ascent of the Messner Route (the mountain’s famed ice route). But the fins were all but gone already.

Gadd sees the issue back home, too, with North American glaciers retreating at an accelerating rate. Montana’s Glacier National Park, the largest collection of permanent ice in the Lower 48, has only 25 remaining glaciers, down from 150 in 1850. The glaciers that crown Rocky Mountain National Park and Glacier Bay National Park are in the same sinking boat.

Sure, that loss of ice is a problem for climbers, Gadd says, “but the bigger issue is for cities that rely on seasonal ice- and snowmelt for their water.” — Graham Averill

The Cowboy Conservationist: Greg Hendricks

Greg Hendricks has been hunkered down, silent, amid Nevada desert scrub for hours. Now, finally, the latter-day cowboy’s quarry is near. He stealthily shoulders his rifle, adjusts its sights and shoots a wild mustang mare. And the people who love these horses love him for doing it.

That’s because he’s firing darts filled with the birth control substance PZP.

See, the Southwest is home to some 95,000 feral horses and burros descended from those brought to the Americas by the Spanish 500 years ago. And as much as there’s no better symbol of unbridled freedom than wild horses, they also graze for 16 hours a day and reproduce prolifically, straining scant desert resources and riling cattle ranchers on both private and public lands.

For five decades, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management has used low-flying helicopters to round up mustangs into pens, which regularly causes stampedes and grisly deaths. Even so, wild herd numbers often increase after a roundup.

“It’s a sad, gruesome thing to see,” says Hendricks, director of field operations for the American Wild Horse Campaign.

PZP is a cheap, safe and humane way to keep herd sizes sustainable. The tough part is getting close enough to a feral horse to dart it, requiring frigid mornings in rugged terrain, plenty of lukewarm coffee and damn good aim. The greatest hazard can be crossing paths with ranchers who harbor a sizable distrust of interlopers, be they animal or human.

Hendricks remains steadfast, building a team that’s darted 1,300 mares with permission on private lands. The next step is to broaden the program onto public lands overseen by the Bureau, which still relies on mass herding.

“These horses are a part of our history,” he says. “They’ve survived for hundreds of years out here, and they’re still surviving. They’ve earned it.” — Adam Popescu

The Hell Fighter: Jeff Denholm

As wildfires ravaged California last August, the CZU Lightning Complex fire began to burn through Bonny Doon, turning the wooded surfers’ haven northwest of Santa Cruz into a particular shade of nightmare.

Cal Fire crews were occupied with other blazes, unable to reach the town of 3,000 for several days. “It was a bad scene, man,” says Jeff Denholm, a Bonny Doon local who leases a fleet of fire engines to the U.S. Forest Service. Fortuitously, Denholm is also the founder and CEO of Atira Systems, maker of the next-gen, non-toxic fire suppressant Strong Water.

The gel-like substance, which clings to trees and smothers flames, is intended to be delivered via a helicopter-mounted cannon—an item in short supply as hell approached. But Denholm did have a truck rigged to spray the suppressant. Ignoring evacuation orders, he and his neighbors managed to save many homes, including his own.

The battle brought new urgency to Denholm’s work developing tactics to fight a frightening trend. “Wildfire propensity is forecast to increase tenfold in the next three decades,” says Denholm. “That’s six months of smoke a year. We can’t live that way. We need this technology.”

Denholm contends that his innovation counters these hotter, faster-burning mega-blazes better than the typical method of planes dropping red Phos-Chek retardant powder ahead of a fire’s advance. Departments as close as San Bernardino County, CA, and as far away as Australia, agree and have added Strong Water to their wildfire-fighting arsenals. — Chris Van Leuven

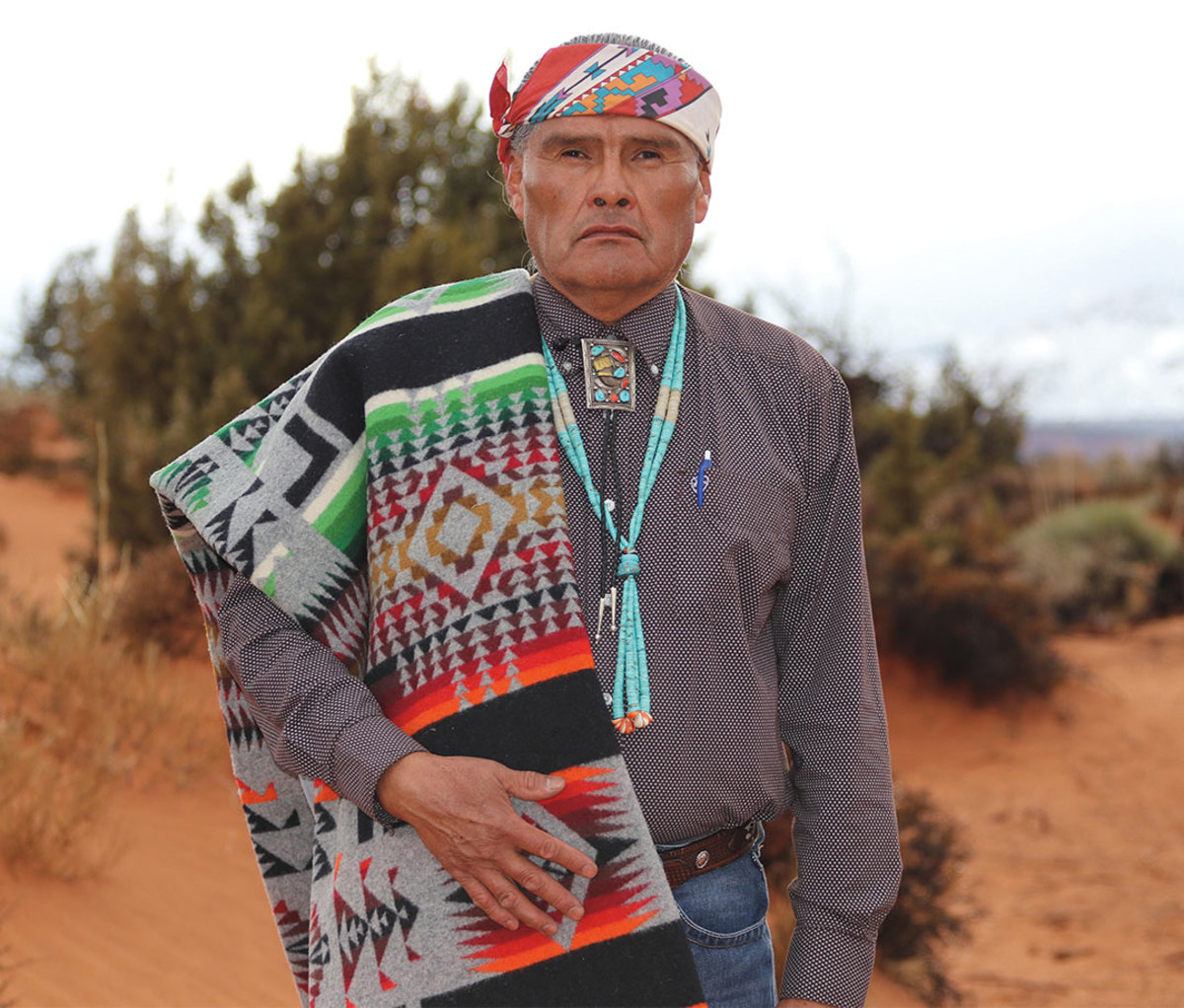

The Native Voice: Hank Stevens

Hank Stevens has already witnessed the toxic contamination caused by a 20th-century boom in uranium mining on his cultural homeland—sacred sites and hunting grounds in southeastern Utah. As president of the Navajo Mountain Chapter of the Navajo Nation, he has been working for years to save the nearby public lands of Bears Ears National Monument from the same fate.

Stevens also co-chairs the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, made up of Hopi, Zuni, Navajo and Ute tribes. As its Navajo representative, he’s organized decision-makers and traveled to spread the urgent message of what’s at stake. Bears Ears is a sacred site not just for the tribes, but anyone wishing to experience the glories of its natural state.

The coalition successfully petitioned the Obama administration for federal protections for Bears Ears, the first designated monument proposed by Native American leaders. And after the Trump administration’s drastic reduction of Bears Ears’ protected acreage, the group steadfastly defended the region from an aggressive oil, gas and mining agenda.

The result? President Biden’s executive order to review again the monument’s boundaries.

“The next opportunity is now,” says Stevens. — Cassidy Randall

The Super Arborist: Drew Peterson

When wildfire whips through a forest, tens of thousands of giant pine and fir trees, often still burning, must be felled in order for ground crews to gain access, and locals to safely escape.

“These are the jobs you don’t tell your mom about,” says Drew Peterson, Oregon-based tree climber and self-pro-claimed Swiss Army knife for the U.S. Forest Service. “You are working to get trees down that are nearly burned through. The risk can be pretty staggering.”

Though Peterson’s specialty is taking out such hazardous trees, the USFS also has tapped the elite rock climber for another vital conservation task—saving endangered tree species that are threatened by fire, drought or disease. Often his goal is to return to terra firma with critical genetic material that gets distributed to seed-bank vaults around the world.

“I can’t really call myself an environmental activist,” admits Peterson. “My personality is more keeping my head down and hands dirty.”

For one mission, he packed his climbing gear and shipped out to California’s Channel Islands National Park to collect cones from the Torrey pine—one of the most endangered tree species in North America. Despite high winds and long pack-outs, he returned with bags full of the pineapple-size cones: “It was basically the arborist equivalent of a Patagonian climbing adventure,” says Peterson. — Nancy Bouchard

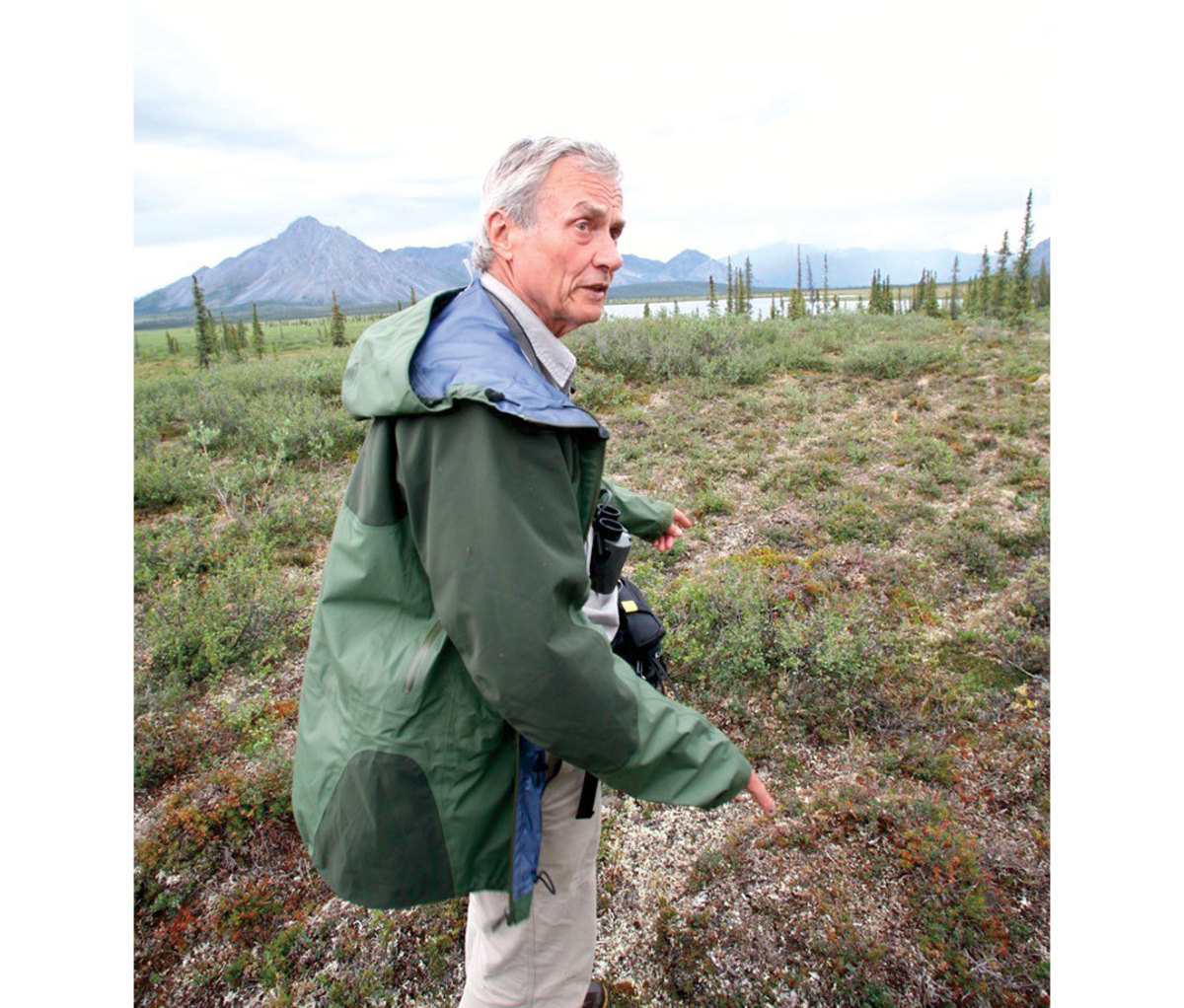

The Wilderness Sheperd: George Schaller

Explore the wilds with George Schaller—the world’s greatest living field biologist—and you’ll quickly pick up on his indefatigable sense of mission. While trekking the Arctic in 2006, the then-septuagenarian moved with the same enthusiasm and limber grace as the grad students in his wake, pausing only to pull apart grizzly scats, measure tree trunks and note all in his pocket-size journal.

For more than six decades, he’s endured countless storms, hellacious insects and civil wars in a storied career that he calls “roaming around watching animals.” His gentle yet tenacious advocacy fostered the creation of more than 20 refuges around the globe that protect large creatures besieged by habitat loss, over-hunting and climate change. Armed only with notebook and camera, working in close quarters amid wild teeth and claws, Schaller believes that focusing on charismatic megafauna can extend protection to all important species on public lands, even down to scant arachnid species like the newly discovered Liocheles schalleri, given his surname.

Possessed of less aversion to self-promotion, George Schaller could be a household name. His 1950s graduate fieldwork in Alaska led to the creation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. He steered Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey to their breakthrough work with great apes. And after leading his friend Peter Matthiessen through the Himalayas, he became the semi-anonymous protagonist “GS” in Matthiessen’s 1978 classic, The Snow Leopard. Schaller himself would write 22 books and publish hundreds of articles that further buttressed his devotion to saving wildlife and public lands.

Now in his 80s, walking near his New Hampshire home in characteristic, watchful strides, he mentions a Colombian colleague who wants him to visit wildlife there. Then China, Brazil, Ecuador, maybe Guyana. “I choose where I can do something useful,” he concludes. And asked when he’ll stop and relax, he waves his hand impatiently. “When I die,” he says, “I retire.” — Jon Waterman

The Border Guardian: Gabe Vasquez

Gabe Vasquez first learned a love for the outdoors from his grandfather—hunting in Mexico’s Sierra Madre and fishing on the Rio Grande. After immigrating to the United States at age 10, Vasquez watched the magnificent Grande, the lifeblood of so many border communities, diverted and divided as the river became a front in battles over immigration policy.

Now a city councilor in Las Cruces, NM, Vasquez founded the Nuestra Tierra Conservation Project in 2017 to ensure that those same communities maintain access to public lands, and play a central role in their conservation, rather than remaining excluded.

He guides decision-makers to experience this marginalized region that encompasses some of North America’s most biodiverse landscape of grasslands, deserts and forests—home not to drug runners and migrants but to mountain lions and mule deer.

He’s also fostering the next policy influencers, expanding opportunities that “make you love a place” by taking local Hispanic youths rafting and hunting, or hiking Organ Mountain Desert Peaks National Monument, which he played a key role in establishing in 2014. “It’s incumbent upon us to make sure that more of our young people can have those experiences. — Cassidy Randall

Young Guns: The Next Generation of Public Lands Defenders

1. Tanner Saul

Age: 25

Homebase: Missoula, MT

Cause: Tracking wildlife

Purpose: To tag a 500-pound grizzly for study, somebody has to jump out of the helicopter—often it’s Saul, who started collaring mountain lions with the Park Service while still in high school. That led to working with wolves in Montana and caracals in Africa, always looking to make a difference, “whether it is protecting [wildlife] from disease or extinction or human pressure,” says Saul, who now hosts A Wilder View on Montana Television Network.

2. Sammy Gensaw

Age: 26

Homebase: Yurok Reservation, CA

Cause: River revival

Purpose: Gensaw doesn’t just view the upcoming demolition of four of the Klamath River’s six dams in California and Oregon as the culmination of a decades-long struggle. The cofounder of the Ancestral Guard, an outdoors-oriented network of indigenous peoples, calls it no less than a “restorative revolution” that will help develop local foodways and teach youths the traditional fishing skills strained by the dams’ decimation of salmon and steelhead populations.

3. Fred Campbell

Age: 33

Homebase: Seattle

Cause: Elevating climbs

Purpose: Playing football at Stanford, Campbell suffered a broken neck. When he healed and took up climbing instead, he found a sport with the power to change lives—especially so as a person of color in the vertical world. The data scientist and team climber for The North Face now uses his platform to inspire new climbers. The more diverse the backgrounds in the outdoors, Campbell explains, the stronger the population “to protect public lands and fight climate change.” — Nancy Bouchard

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/3xxGXlG

No comments:

Post a Comment