In a typical year, Pete Oswald, the New Zealand-born freeskier and photographer will chase an endless winter across the hemispheres. He and his wife, Sophie Stevens, will shred mountains on three or four continents. But 2020, as we know all too well, is not a typical year. In a sense, his world is shrinking.

Oswald and Stevens have yet to leave New Zealand since COVID-19 prompted strict border control measures. The other reason their world feels a bit smaller these days is because they now share the tiny house they built in Queenstown with a third resident. The couple welcomed their first child, a daughter named Tula, in May. Despite major life changes, parenthood and a pandemic have not changed their intrepid lifestyle. Their physical space may be more confined, but their ambitions are bigger and bolder than ever.

Pete Oswald Is on a Mission to Reforest Madagascar

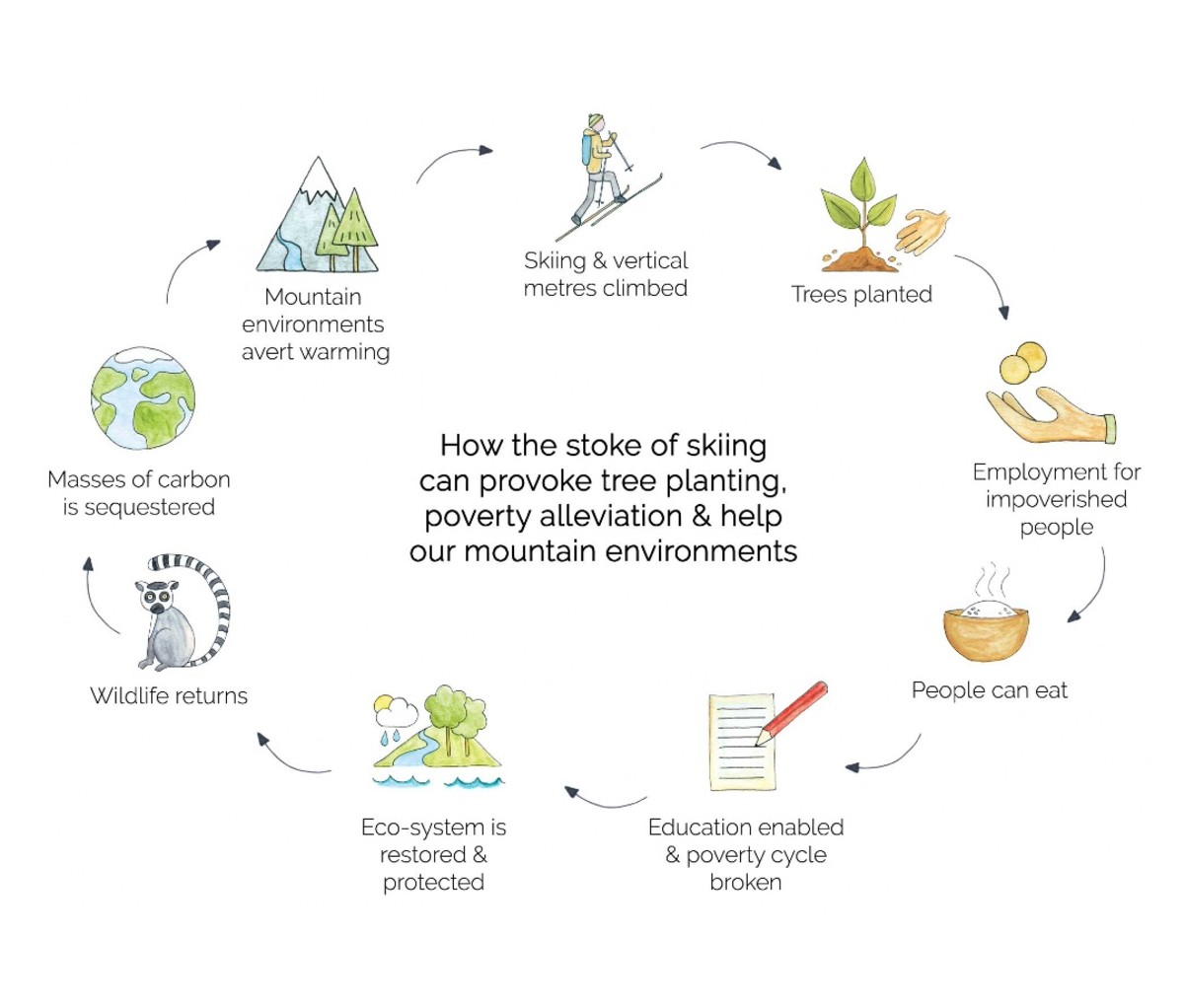

This June, Oswald launched “Ski for Trees,” a campaign aimed at supporting vital reforestation efforts in Madagascar. He proposed to hike and ski 20,000 vertical meters by the end of September to raise funds to plant 20,000 trees. A Kiwi freeskier confronting an ecological crisis in Madagascar may seem like an odd headline, but Oswald is a globalist when it comes to environmentalism.

“At the end of the day, we all breathe the same air,” he says. “So their problem is our problem is everyone’s problem.”

And that problem is dire. Geologists believe Madagascar has lost 90 percent of its forests since humans first arrived on the island. The consequences of this loss are devastating and abundant. Madagascar has an extremely high concentration of endemic species, plants and animals that are distinctly native to the island. Deforestation has pushed many of these species, including the famous Lemur, to the brink of extinction. Beyond this grave threat to biodiversity, deforestation has hastened global warming. Trees are carbon sinks, which means they sequester carbon and help slow the release of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere. Reducing carbon emissions is critical to the health of our planet. (And also the future of skiing).

Unlike other severe deforestation hot spots, such as Brazil, the source of Madagascar’s emergency is not unbridled greed or industrial agriculture run amok.

How Pete Oswald Is Helping to Rebuild Ecosystems and Alleviate Poverty by Maintaining Ski Stoke

“The root cause of deforestation in Madagascar is 2,000 years of humans basically trying to survive,” Stevens says.

Most of Madagascar’s trees have fallen at the hands of its impoverished people. Desperate to feed their families, farmers cut down swaths of forest, then burn the wood, using the ashes to fertilize degraded soil. This is known as slash-and-burn agriculture.

During Oswald and Stevens’ first visit to Madagascar, they were astounded by the level of abject poverty. Their travels have taken them to many destitute parts of the world, but they had never seen so many people scraping by on so little.

“Madagascar is one of the poorest countries in Africa,” Oswald says. “It makes Sri Lanka look like central London.” (In 2013, Oswald and Stevens biked across Sri Lanka to raise money for a pre-school in a region ravaged by civil war and natural disaster.)

Scores of children begging in the streets made it easy for Oswald and Stevens to empathize with the plight of the Malagasy people.

“If it comes down to it, and there’s one tree left that you can chop down to feed your family, maybe sell some charcoal in the market, what do you do?” Oswald asks. He pauses and looks down at his daughter who is napping peacefully in his arms. “You cut it down, obviously. What we learned by going there, and it’s really hard to understand before you go, is that the poverty cycle has to be broken. You’ve got to attack the poverty before you can effectively fix the deforestation.”

In 2016, Oswald and Stevens launched a stationery business called Little Difference. Oswald oversees operations and Stevens, a talented artist, designs the cards and other products using 100 percent recycled paper. They started the company as a way to fund their adventurous lifestyle––even with sponsors like K2, Smith, and Icebreaker, freeskiing isn’t the most lucrative profession––but it quickly became profitable and they formalized a commitment to raising money and awareness for reforestation.

After conducting extensive research, they partnered with Eden Reforestation Projects to focus their efforts on Madagascar. But why there?

“It’s where the need is the greatest and where we can make the biggest impact for the investment,” Oswald says.

What sets Eden apart from similar charities is that they employ local residents to plant, cultivate, and protect the trees. Oswald believes this is critical to breaking the poverty cycle.

“When you involve the people and have them invested as stakeholders in the forest, then that changes everything and makes for a way more holistic process. Their livelihood becomes tied to protecting the trees.”

As part of their business model, Little Difference pledges to plant one tree for every one product sold. “Since we sell paper products, even though it’s on recycled card,” Stevens says, “we want to plant trees to help grow the paper back.” They’ve helped plant over 90,000 trees since starting their business.

It was in this spirit that Oswald conceived of “Ski for Trees.” He also saw it as an opportunity to do some immediate good with his passion.

“Skiing, for me, has been an exhilarating and rewarding journey, but it’s also a privileged and narcissistic existence,” Oswald says. “Skiing is solely dependent on the environment, so I just thought, wouldn’t it be cool if every meter climbed was a tree in the ground?”

The pandemic has not hampered his ability to log meters. Queenstown, often hailed as “the adventure capital of the world,” is the beating heart of New Zealand’s vibrant ski scene. The jagged Southern Alps, the highest mountain range in Australasia, make it a well-endowed winter wonderland. Oswald’s tiny house is nestled at the bottom of Coronet Peak, one of the city’s two major ski fields, so access to world-class skiing is no problem. But he’s had to learn how to navigate unfamiliar domestic terrain.

Pete Oswald on Striking the Balance Between Big Risks and the Big Responsibilities of Fatherhood

“This fatherhood thing is very new to me, so I’m negotiating other responsibilities and just getting what I can when I can,” Oswald says of finding time to ski. Like all productive men, he’s routinized a system to help achieve his goals while being an attentive partner and father.

Skiing is an exhilarating and rewarding journey, but it’s also a privileged and narcissistic existence.

On a typical climbing morning, Oswald rises before the sun. He makes a bowl of porridge for Stevens––“With all the trimmings, of course: honey, blueberries, yummy stuff.”––and scrolls through forecasts before contacting ski patrol for an updated avalanche report. If everything looks good, he’ll either drive to the base of the mountain with friends or thumb a ride if he’s flying solo. “I don’t like to be that guy driving around in his car by himself,” he explains.

Oswald beams as he recounts a recent morning at The Remarkables, Queenstown’s more iconic ski range. “I went up with my good mate Jeremy Lyttle. We hiked Single Cone, the highest peak in Queenstown. Had some good yarns, got to the steep part, put our crampons on, got our ice axes out, and eventually stood at the top of the big peak. Then we had a bloody good ski down.”

Oswald tries to fit two climbs in each outing, but he always makes it home for second breakfast. “That’s when I’ll relieve Soph and have some Tula time,” he says. His biggest takeaway from the early days of parenthood is a profound appreciation for mothers.

“They are absolute wonders of nature,” he marvels. “Just watching Soph with Tula—and the time and effort and the crazy things the mothering body can do is amazing. I need to give my own mother a lot more love and credit.” Stevens, it’s worth noting, is a badass. When I spoke with Oswald, she was busy tearing up track on her mountain bike. She’s also a fearless longboarder.

Fatherhood has given Oswald reason to reflect on the risks that are inherent to his profession. Having represented New Zealand in the World Qualifier Series, he’s tackled some of the toughest terrain on the planet. His body has paid a heavy price for this pleasure. He rattles off the injuries he’s sustained as casually as reciting a grocery list: “I’ve broken my back twice, cracked sternum, broken collarbone, broken scapula, dislocated elbow, about 20 concussions, brain hemorrhage, snapped calf muscle, chipped patella.” He’s also had four surgeries as a result of tearing the meniscus in each knee…twice.

After the third surgery, the doctor told him he would never run, jump, or ski again. Oswald was devastated. The doctor’s advice? “Adopt a more sedentary lifestyle.” Oswald’s reaction? Seek a second opinion.

“It took two years of rehab with more open-minded health professionals, but I got back to 100 percent again,” Oswald says. “That was a hard road.”

Has he considered slowing down now that he’s a parent?

“Someone actually called me out after seeing a recent video. They said I shouldn’t be out skiing because I’m a dad now. If I really loved my daughter I wouldn’t put myself in that position.” He understands the general nature of these concerns, but he disagrees with their monochromatic portrayal of risk.

“Risk is relative,” he says. “I’ve talked about this a lot with my friends. Your risk assessment and risk management is something you build up over your whole life. Everybody does it. Down to the person who only goes down to the corner shop once a week. They assess how they cross the road or whatever. It’s no different with skiing. It’s all about trusting your assessment of risk.”

Oswald, who just turned 35, has been skiing for over 30 years. His conviction in his instincts and decision-making process is unwavering.

“It’s all about constant monitoring. You look at any situation and try to foresee the worst scenario. If the worst possible scenario is not a good one, or can’t be easily mitigated, then you’ve got to look at another avenue,” he says. He thinks for a moment and adds, “Generally the riskiest part of any mission we do is the driving to get there.”

Last winter, Oswald set out with three of his best friends to achieve a lifelong goal. They hoped to climb and ski New Zealand’s highest mountain, Aoraki/Mount Cook. It’s considered one of the greatest and most unobtainable descents in the world. “It was not a likely scenario that we were going to make it to the top. It was definitely on the higher end of all our technical abilities. We watched the weather window for a long time.”

When the window opened, the group took their shot. The final ascent started at midnight. Armed with headlamps, pick axes, and staunch faith in each other, they left their ice caves and slogged through the darkness. The journey was perilous. After scaling a nine-hour “no fall zone” fraught with menacing crevasses, they reached the summit.

“It was the pure essence of working extremely hard for something, then reaping the reward,” Oswald says. “It’s a massive buzz to be on top of this mountain after navigating all the technical parts and fear. And then we got to ski and rip down in perfect powder conditions at high speed.”

This winter, Oswald isn’t chasing any bucket list descents. His singular ski focus is on accumulating meters and planting trees. He’s overwhelmed by the support “Ski for Trees” has received so far. As of August 24, Oswald has raised funds for 42,306 trees, shattering his initial goal of 20,000. The campaign goes until September 30 and Oswald has no intention of slowing down.

“I’m looking for 100,000 trees now. That’s the new goal,” he says. “People always talk about a six-figure salary. This is the new six figures. Six figure trees. That’s when you know you’ve made it.”

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/3aXYOaq

No comments:

Post a Comment