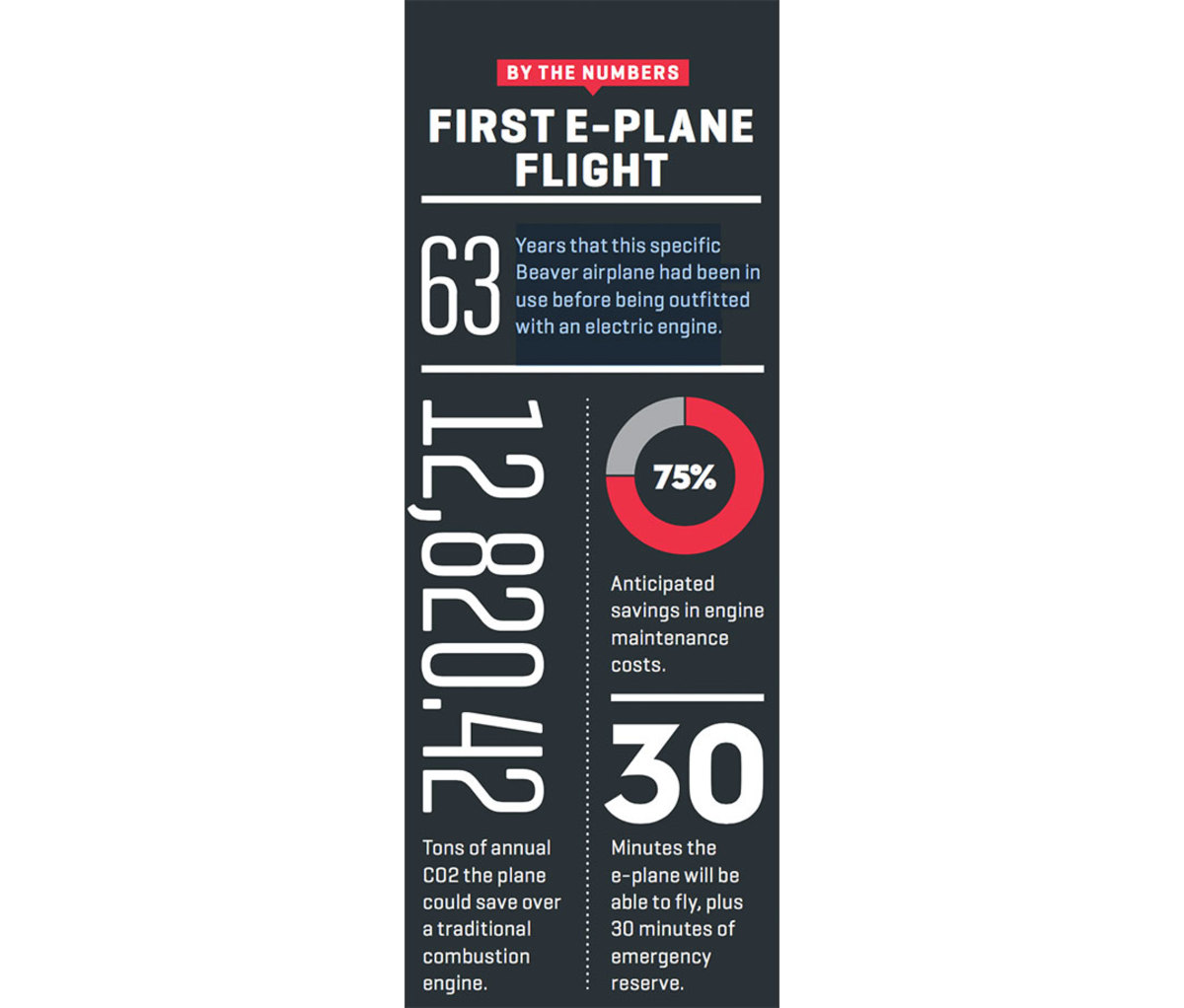

IT WAS cold on the morning of December 10, 2019, in Richmond, British Columbia, when 63-year-old pilot Greg McDougall took off in his 63-year-old floatplane and flew into history. As far as flights go, it was wholly unremarkable. McDougall, the CEO and founder of Harbour Air—the world’s largest seaplane airliner, based in Vancouver, Washington—was in the air for about 10 minutes. And the plane, a De Havilland DHC-2 Beaver, was constructed two years before Sputnik was shot into space. Its new paint job, however, hinted at its exceptionalness: bright blue and green, with technical-looking graphics on its nose.

“This is what the motor, batteries, and electrical wires look like,” McDougall explained before the flight, pointing at the schematic, which depicts a 750-horsepower (or 560 kW) electric propulsion system.

With a crowd gathered at the edge of the Fraser River, McDougall took off in the floatplane for its debut flight as potentially the world’s first all-electric commercial passenger aircraft, and from the get-go, it was clear something was different. With no internal combustion engine burning fuel, there was no exhaust and no deep piston rumble. The air was remarkably calm, and the emissions for the four-minute flight: zero. It wasn’t exactly a Wright Brothers moment, but in the morning air, it must have felt something like the first flight in Kitty Hawk: quietly revolutionary.

“TECHNOLOGY WILL SAVE US,” McDougall is fond of saying. He first told me this when I met him in an airport hangar two weeks earlier. Around us, technicians and mechanics were working on a variety of floatplanes in various states of disassembly. At the center of it was the De Havilland with its electric motor. With roughly 170 other electric-flight projects underway around the globe, Harbour Air pulled ahead of the others by introducing perhaps the most novel concept out there: simply electrifying an old, dependable plane.

“We’re just making old technology as clean as possible,” says McDougall.

Rather than building and certifying a plane from the ground up—a long and expensive process—Harbour Air simply needs to certify existing planes with its new propulsion system. This relatively quick process may see passengers boarding e-planes in as little as two years. After that, Harbor Air will begin outfitting its entire fleet—40-plus planes that carry out 30,000 flights annually, primarily taking business commuters between Vancouver, Victoria, and Seattle—with electric motors.

Manned electric flight isn’t a new idea. It’s been around since the 1970s with single-person prototype planes. What’s changed is the urgency brought on by the climate crisis. The aviation industry contributes an estimated 2.4 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions. As someone who had the ability to be part of the solution, McDougall felt compelled to do something.

“I just thought somebody had to pioneer the next step,” he says. “It’s going to be a difficult road, but I’m used to that.”

Born in Southern California to Canadian parents, McDougall first traveled in a plane as a kid. “I realized then that’s what I wanted to do,” he says. Flying school followed high school, along with his first job, as a bush pilot in the remote north.

In the early 1980s, when a recession hit and McDougall found himself unemployed, he decided to start his own airline. He leased a few of floatplanes with a partner. “We had no business experience and not much of a plan,” he says. But McDougall did know the kind of company that he’d want to fly for. “In those days, the bush pilot mentality meant taking risks that didn’t need to be taken,” he says, describing pilots who flew in bad weather with overloaded planes. “We wanted people to trust us enough to put their kids on our planes.”

As the company transitioned from flying charters for the lumber industry into a regional commuter airline, McDougall realized that earning customer trust also included protecting the places they were based. “We fly over these spectacular glaciers and forests every day, and we have a role in keeping them that way,” he says.

One of the first steps to help safeguard the environment came in 2007 when, through offsets, Harbour Air became North America’s first fully carbon-neutral airline. But McDougall knew the aviation industry could do more. “I drive a Tesla,” he says. “Plus, I’d been reading about the electrification of transportation. I thought, Why wouldn’t we put this in an aircraft?”

Initially, McDougall says they were stymied by the costs: Established aviation companies were making electric motors only as a sideline, and none were the right match. But in February 2019, Roei Ganzarski, the CEO of MagniX, a Redmond, Washington–based electric-propulsion technology firm, walked through the door and said he wanted to put his motors in a plane. When the two companies decided to get a plane flying by the end of 2019, news of the project created positive buzz—and plenty of naysayers.

“The traditional aviation industry doesn’t really embrace change,” McDougall says. When he was inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame in May 2019, he used his speech to let the aviation establishment know that while he appreciated the honor, his major contribution—the electrification of commercial flight—was still to come.

“I could almost hear the harrumphing,” he says, “which of course was inspiring.”

IN DECEMBER, as the Beaver touched down, a cheer rang through the crowd gathered along the Fraser River. When McDougall hopped out of the plane, he and Ganzarski hugged. At the ensuing press conference, Ganzarski proudly proclaimed: “We just flew the first electric commercial aircraft. Next year, there’ll be more,” he said. “Call it competition. Call it cooperation. It’s the future.” In other words, this flight is really just the beginning, and there’s a long road ahead. Critics point out that fossil fuels are 40 to 50 times more power-dense than current batteries, and batteries just don’t last long enough for regular flights. Charging them can take too long. But Ganzarski believes change will come quickly. “Before Tesla,” he says, “no one invested in batteries for cars because there was no car to use them. The same thing will happen with aviation.”

Harbour Air is flying small planes on short routes, so McDougall figured current batteries would already work for them—and his change may serve just as inspiration for other companies. “The aviation industry is safety-focused and risk-averse,” says Lynnette Dray, a senior research associate at University College London’s Energy Institute. “So there’s a lot of value in getting prototype models to market, so the technology has a chance to become familiar and trusted.”

McDougall is even more optimistic.

“Overall the 10,000-hour life of a motor,” he says, “a conventional engine would cost around a million bucks in maintenance, whereas an electric motor should cost us virtually nothing.”

Harbour Air is now deep into the certification process and has begun accelerating its test flight program, taking the e-plane into the air on a near-weekly basis. “People may not see it coming, but this is a major movement,” says McDougall. “People are intelligent enough to solve all our issues with technology—as long as we don’t do something stupid in the meantime and screw it all up.”

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/2ZFRtc4

No comments:

Post a Comment