The Baja 1000 is one of the world’s toughest off-road races, and few are talented (and crazy) enough to run it solo on two wheels. We follow along as one madman goes for glory.

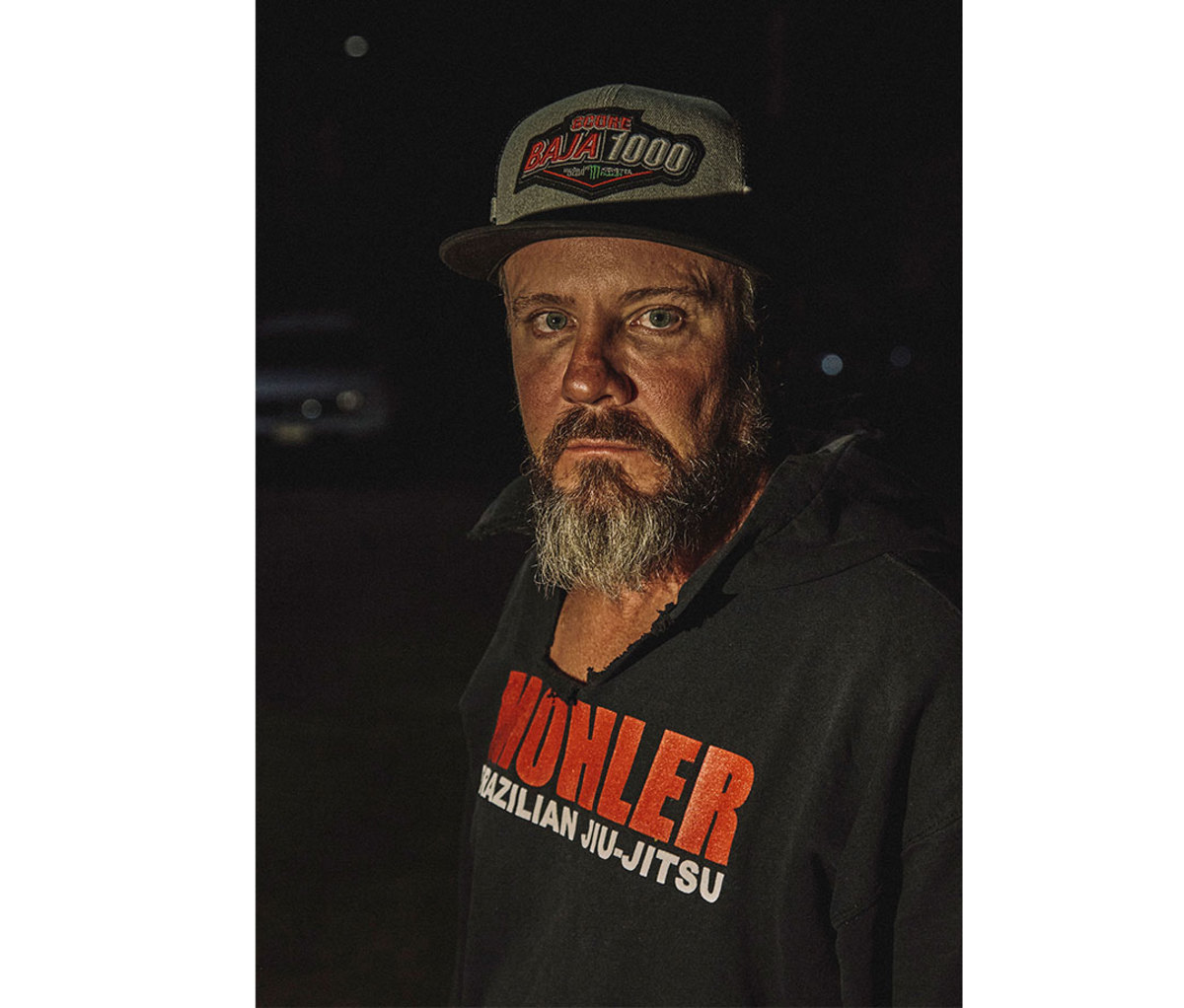

RICK THORNTON is fuming. Over the past 18 hours, the veteran dirt bike rider has covered more than 500 miles of hard terrain, carving his way through a relentless gauntlet of sandy washes, ruts, and steep mountain passes that combine to make the Baja 1000 arguably the toughest off-road motorsport race in the world. Whereas most other pro motorcycle racers are competing on teams of four, Thornton, 52, is trying to “Ironman it”—complete the race solo. Having ridden more or less nonstop since the race’s predawn start, he just battled two rivals over a nasty section of bumps to give himself a cushion coming into the most important pit stop on the course.

And he can’t find his crew.

“I’m pissed off, my mind is playing tricks on me, and I need a break,” he says. “Where is my team?”

His hands are numb, and his knees are buckling from constantly riding up in the attack position. The bike is even worse off: His front brake is slipping, and the taillight and GPS are busted. Then there are the damned trucks. Released seven and a half hours behind the motorbikes, the trophy trucks, as they’re called—each one a growling 1,000-horsepower juggernaut—would be catching up any minute now, thrashing an already sinister racecourse.

A fast-talking Oklahoman with cool-blue eyes and a grizzled goatee, Thornton has proven reserves of willpower. As a 5’11” freshman in college, he’d walked onto the 1985 University of Oklahoma football team, the year they won the NCAA title. In his 30s, he picked up competitive jiu-jitsu and, at 45, took gold in a world championship event. The first time he ran the Baja 1000, in 2006 with his brother, his team winged it and finished strong after going out and drinking “more than a few beers” the night before.

But two previous attempts at running it solo had taught him that success demanded more than a never-say-die attitude: The first ended in physical collapse and near death; the second in disqualification for finishing over the allotted 36-hour time limit after one too many crashes.

Now he scans shadowy roadside camps for a familiar face. “I’m pretty much screwed,” he says, with another 300 miles to go before the finish line.

SOMEWHERE BETWEEN an ultramarathon on wheels and a fever dream, the SCORE Baja 1000, as it is officially called, is an infamous race through the Mexican backcountry where anything still goes. Inspired by a company-sponsored project to test the durability of Honda motorcycles, the “granddaddy of off-road races” has been run on the namesake peninsula since 1967. It has attracted top competitors from around the world and Hollywood motorheads including Paul Newman, James Garner, and Steve McQueen.

Big-brand sponsors and cameras have followed, but the rogue, egalitarian spirit endures. Million-dollar trophy trucks share the course with motorcycles, quads, and stock Volkswagen bugs. Public roads are never shut down, meaning any local hero can jump onto the course. Nearly half of the competitors who start it don’t finish, and the prize money is a pittance. Yet every November, top riders, among them champions from NASCAR and Formula One, continue to flock to this desert crucible.

“When you finish a race in Baja, it’s like you’ve lived 100 lives,” says Roger Norman, the 2008 trophy truck champion and owner of SCORE (Southern California Off-Road Enthusiasts) International, the promotion company that organizes the race. “There’s nothing so exhilarating as doing something extremely dangerous and surviving. If this was super safe, all these guys wouldn’t be here.”

In the days before the race, downtown Ensenada, its starting point, becomes a raucous carnival. Thousands of fans throng streets thumping with cumbia music and the rumble of supercharged engines. The sweet smell of hot churros mingles with racing fuel as competitors go through final checkups and parade down the main strip to shouts and whistles.

“These men are playing with their lives,” says Jesus Romero, 47, a sombrero-wearing restaurant owner from Ciudad Juarez who comes out for the race every year.

The Baja 1000 is run either as a point-to-point, north-to-south race or a northern loop that starts and ends in Ensenada. The 2019 running is an 800-mile loop, and it’s shaping up to be a bruiser. Rains lashed the region for four straight days, forcing a delay for only the second time in 52 years. Entire sections of the course are washed out, some of them underwater.

The night before, all the teams convene at a luxury hotel to learn the details of this year’s race. There are 264 entrants in the contest, and the lobby is abuzz with speculation about course changes and further delays. Amid the swarm of hoodies and ball caps is Robby Gordon, the former NASCAR bad boy, trailing an entourage. Mark Samuels, of the winning 2018 Honda pro moto team, is walking unaided after breaking both femurs in a race seven weeks back. He gets some friendly ribbing from Toby Price, an Australian phenom who won the 2019 Dakar rally with a broken wrist.

Meanwhile, Rick is at his Airbnb rental sleeping (or at least trying to) with an IV pumping saline into his arm. He figured, correctly, that the race would proceed in the morning, and he needs every edge he can get to compete with guys half his age. In 2017, on his first Ironman attempt, he’d managed to complete 80 percent of the race with a broken foot and was on track for a top-three finish, until his kidneys started failing due to overexertion. When his crew found him, Thornton was going blind and barely able to move, still trying to climb back on the bike.

BRAAAP BRAAAAAP. Racers are taking off every minute into the predawn chill. No crowds, no hype, just revving engines and hard stares. “A lot of tough guys out here,” says Thornton, edging up to the starting line. “Let’s get it on.” At 3:17, he gets a green light and vanishes around the corner.

The first stretch is a 200-mile dash down the peninsula. Thornton settles into a steady groove to avoid early mistakes. After passing several racers early on last year, he got carried away and hit a jump at around 60 miles per hour, landing on a rock and dumping face-first. The crash cracked his helmet, bent his handlebars, and had blood squirting out the IV hookup in his arm, “like a stuck hog.” He kept going but never fully recovered mentally. This year, the heavy mud is pulling on the bike, a grind that Thornton is well prepared for.

When you finish a race in Baja, it’s like you’ve lived 100 lives. There’s nothing so exhilarating.

For the last six months, he’d held to a regimen of long desert rides, weight training, and beach runs to build up his endurance. He kneaded rice to harden his grip, an old jiu-jitsu trick. And he packed on an extra 10 pounds of padding to avoid a kidney-failure relapse. His bike, by contrast, is lean. Thornton races a bored-out 2016 KTM 300cc two-stroke, stripped down to 214 pounds, about a hundred pounds lighter than the standard four strokes.

The real racing begins at around mile 220: a grueling, technical mountain traverse that climbs 7,000 feet over a hundred miles. “If you’re weak mentally,” he says, “you’ll break your ass or fall off a cliff.” On the ascent, he starts “swapping paint,” or dueling, with another game Ironman racer. I ride in the chase truck with his crew. Chad Newman, a nine-time Baja 1000 mechanic, is at the wheel. After a quick pit stop at the start crossover, we have several hours to shoot back up and over the mountains to meet Thornton on the Sea of Cortez side, a tight window that has us running a breakneck race of our own. We’ve already blown past police checkpoints and detoured through a construction site when I spot a swarm of helicopters in the near distance. Suddenly, a streak of dust zigzags up the ridge on our left, like the choppers are strafing it with machine guns.

The trophy trucks have been unleashed. The Baja 1000 is now full tilt.

IN THE PIT STOP area around mile 542, a Mad Max–style spectator party has popped up in the desert blackout. Floodlit trophy-team stations with six-man crews and hydraulic tools await the trucks, while speaker boxes blare 50 Cent and ranchero ballads and more than a dozen bonfires rage, surrounded by revelers. The Baja remains a free-for-all where anyone can stake out a place along the racecourse and get dangerously close to the action.

“This race is for the people,” says Fernando Amao, 52. Seated with his 11-year-old grandson, he says he’s been coming here since he was the boy’s age.

Around 9:30 p.m. the first trophy truck screams past in a storm of dust. Everyone cheers. But still no sign of Thornton. We’d expected him to arrive a half-hour before, and his team is getting worried. “This is catastrophic,” one member whispers. His wife, Brandie, paces back and forth. Momentum is everything on such a long, sleepless haul. Lose your way, or stop too long, and you might never recover.

I walk over to a race tent and eavesdrop. We got a bystander hit by a trophy truck, crackles a voice on the radio. Fans are injured as frequently as racers, though no one is immune: During the 2013 race, champion racer Kurt Caselli died after colliding with an animal. Minutes later, a young man from Colorado walks up to report his teammate has just had a high-speed crash in a remote area, breaking his collarbone and several ribs. The radio operator scrambles an ambulance to pick him up but warns it could take hours given the road conditions.

After another 30 minutes, Thornton shows up, and Brandie, a registered nurse, puts him in her truck’s cab and starts administering an IV drip to combat dehydration. Unable to find us after two hours of scanning and yelling out, Thornton had stopped further down the road and asked another crew to call Brandie. Six men tried to reach her, and one eventually got through. Turns out the team was just two miles away. Thornton blew up. “It’s frustrating,” he vents. “I hate being lost.”

He’s cooled off some by the time another trophy truck surges by, while he waits for his bike to get tooled up. He gives it the finger. “I love trophy trucks,” he says.

AT THE FINISH LINE, racers have been staggering in all morning, vehicles in various states of disrepair. We wait past noon, and Brandie is beginning to worry again. The night before, his GPS conked out a second time, and when we met him at the penultimate pit stop, he mentioned two crashes. “I’m tired, I’m hurting, I need more pain pills for my knees,” is about all he managed to grumble.

As we consider the worst, he rounds the final bend and in short order crosses the finish line. Thornton’s time of 32:09:26 is enough, when the official results are later tallied, for fifth place in his class. On the big stage, he hugs out the team and receives a finisher medal.

Thornton buys a beer from the first vendor he sees and takes a slow walk back to his truck, past street plaques honoring Baja champions. He’s now a bona fide Ironman.

“I’ve done some tough races, but that was the gnarliest Baja I’ve ever ridden,” Thornton tells me three weeks later, shaved and chatty again. He ran a clean race for the first half and figures the lost time that night in the pits cost him a top-three finish. The thought still gnaws at him. “I have only myself to blame,” he says.

What about next year? The 2020 race, I remind him, is going to be the classic Baja 1000 point-to-point. “I’m getting old, man,” Thornton sighs. “At my age, it’s such a challenge.” The endless months of prerunning, the hills and sand sprints, the toll on his joints. “Plus,” he deadpans, “Brandie might divorce me.”

Thornton still hasn’t answered the question. I ask again. “I’m retired,” he says, flashing a mischievous smile, “until I change my mind.”

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/3aRFRVt

No comments:

Post a Comment